The Case for Dollarization in Argentina

Since 1945 Argentina suffered the pernicious effects of high and volatile inflation. Only dollarization offers hopes for a lasting cure.

Javier Milei, the leading presidential contender in Argentina’s upcoming presidential elections, has proposed dollarizing the Argentine economy as the centerpiece of his campaign. He is the most popular politician in the country today and is expected to win the largest number of votes on October 22.

The opposition to dollarization of certain interest groups and their mouthpieces in Argentina is not surprising. Dollarization would help put an end to a system that benefits them at the expense of the majority of the population. What was more surprising however, was the reaction abroad. With few exceptions, self-appointed pundits and recent experts on Argentina have been negative on dollarization. Some have argued that a debt default, not dollarization, is the solution to Argentina’s problems, and others, paraphrasing Ecuador’s former president Rafael Correa, have claimed that adopting the dollar would be the equivalent of a monetary suicide. What is missing from most analyses is common sense and an understanding of Argentina’s history and its current predicament.

The first fact that needs to be understood is that the Argentine people have already chosen the dollar as their preferred currency. According to several estimates, Argentines have more than US$200 billion in dollar bills stashed away in safe deposit boxes at banks or at home “under the mattress”. In comparison, peso denominated M3 held by the private sector amounted to less than US$50 billion. This discrepancy reflects spontaneous dollarization. However, due to Soviet-like FX regulations buying and selling dollars is considered a crime. For obvious reasons, nobody in Argentina wants to hold pesos (in the last four years the peso has lost 95% of its value). This not only makes it very difficult for policymakers to stabilize the economy but also imposes significant deadweight costs on society (the round-trip spread in the free FX market averages 3%).

Some economists claim that by adopting the dollar as legal tender, Argentina will lose a) substantial revenues from seignorage, b) the ability of the central bank to act as lender of last resort, and c) the ability to cushion external shocks with FX policy. The reality is that a) most of the seignorage revenues were lost long ago due to spontaneous dollarization, b) the central bank is insolvent and is currently the main debtor of the banking system, therefore unable to act as lender of last resort, and c) in Argentina FX policy has never been used to absorb shocks but rather to repress inflation. As to monetary policy, it has only served to foster instability. In 43 out of 46 years in the period 1945-1991 and in 20 out of 22 years in the period 2002-2023 Argentina had an annual inflation rate higher than 10%. No other country matches this track record.

Economists have long known that it is impossible for an economy to grow with high, persistent and volatile inflation. Keynes famously attributed to Lenin a dictum that he wholeheartedly agreed with: the best way to destroy the foundations of a capitalist society is to debauch its currency. With few exceptions, this is what Argentine policymakers under civilian and military governments have done since WWII.

When it comes to the currency, the Argentine constitution imposes on Congress only one obligation: to do whatever it takes to preserve its value. Politicians have ignored this mandate with impunity. No government run by fiscally profligate politicians should have a monopoly over the issuance or the control over the supply of money.

More than a century ago, John Stuart Mill argued that preserving national currencies as a symbol of national pride was a form of barbarism. Such a medieval conception of money is even less defensible in a globalized and increasingly digital economy. Two hundred years of Argentine monetary history show that the only periods of lasting stability occurred when the national currency was pegged to an international standard. And the experience of 2001 shows that a currency board with a bi-monetary banking system would be easy to reverse, therefore not credible.

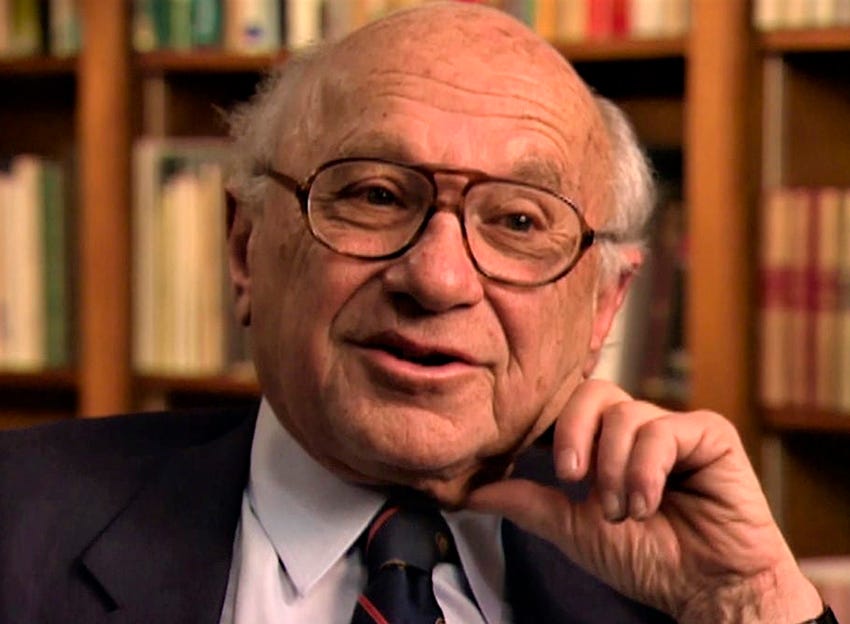

Almost 50 years ago, in testimony he gave to Congress, Milton Friedman made a strong case in favor of dollarizing Argentina: “U.S. policy has been bad, but their policies have been far worse,” he said.

“There are no gyrations in American monetary policy which can hold a candle to the gyrations which have occurred in Argentinian domestic monetary policy. So, the whole reason why tying to a major currency would be an advantage to Argentina is that precisely that it would prevent them from following bad domestic monetary policies.”

At the time, mid 1973, the annual inflation rate in the US was 6,5% and in Argentina over 65%. Today, the figures are 3.5% and 125% respectively.

Not only Friedman, but also Alberto Alesina, Robert Barro, Guillermo Calvo, John Cochrane, Tyler Cowen, Rudi Dornbusch, Steve Hanke, Steven Kamin, Robert Mundell, Kurt Schuler, Larry Summers, Scott Sumner and many other well-respected economists have supported dollarization in countries that have shown themselves incapable of maintaining lasting price stability.

When he was chief economist at the World Bank, Summers summarized the case for dollarization with an apt analogy:

“There are many strategies one could take to prevent disastrous results of reckless driving. One could pad cars well so that accidents are less of a problem… One could “lurch away” and put daggers in steering wheels, giving people a very strong incentive to drive safely. Another tactic is to remove car accelerators so that no one can drive faster than sixty miles an hour. Or one could simply put an end to the issue by taking the train. Likening the possibilities for currency substitution to these options for accident prevention, I believe that the currency-board strategy is analogous to removing car accelerators while dollarization is like taking the train”.

During the nineties we tried removing the car accelerator and it worked well for ten years. Unfortunately, a currency board with a bi-monetary banking system proved vulnerable to reversion by politicians addicted to soft money. In contrast, the experience of Ecuador shows that, with a working electoral democracy, reversing dollarization is very hard and politically costly. It is high time for Argentina to take the train.

Dollarization is neither a mirage nor a magic potion. Structural problems require structural solutions. We need to reduce public spending, deregulate and open the economy and add flexibility to labor markets. We should not ask more from dollarization than what it can deliver. And that is two important things that are key for Argentina’s prosperity. First, by eliminating inflation rapidly, it would provide political support for a program of structural reforms. Second, it would take away from populist politicians one of the most destructive weapons in their arsenal, while at the same time giving the private sector the freedom to choose a sound currency with which to transact, save and invest.

The author is advisor to Javier Milei on matters related to dollarization.

Very eloquent article exposing the reality that sound money is always better, even if you have to import it from abroad. This truth is known to lay people. Only governments have a hard time dollarizing because they lose privilege. It’s time to democratize the privilege of hard currency for all Argentine citizens and reduce the “economic calculus” significantly in one blow. Dollarization is the only way.

Never clearer. It is time for Argentina to put aside socialist ideas and begin the path to freedom.