Implementing Dollarization in Argentina: Why it is necessary to restructure the Central Bank

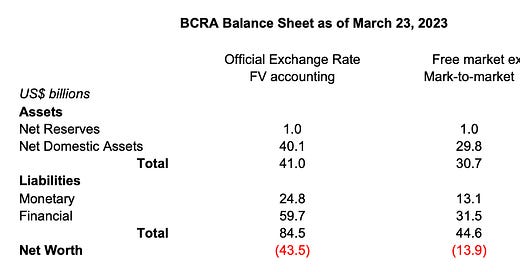

When evaluating the economic feasibility of an official dollarization in Argentina (adopting the dollar as legal tender), many analysts assert that it is impossible at a reasonable exchange rate.1 They reach this conclusion by dividing the monetary base (in pesos) by net reserves (in dollars). This formula supposedly yields the “conversion exchange rate” for a dollarization.

As can be seen in the graph below, in the last six months this “conversion FX” experienced abrupt variations. This was mainly due to the high volatility of net reserves. In August 2022, the resulting conversion FX was close to 15,000 pesos per dollar (clearly unfeasible), and by December, it had fallen to 574 pesos per dollar (when the free-market exchange rate was 355 pesos per dollar).

Ratio of Monetary Base to Net Reserves

This approach is conceptually wrong as it assumes that the Central Bank of the Republic of Argentina (BCRA) has no other assets in its balance sheet but net reserves (or assuming that its financial assets are worthless). Obviously, the value of these assets depends critically on long term fiscal sustainability. We always emphasize that dollarization alone doesn’t solve Argentina’s structural problems and that our proposal has a main underlying assumption that the government pursues an aggressive plan of fiscal adjustment. By eliminating inflation rapidly, dollarization (as Convertibility did in 1991), will generate substantial and lasting political support for a reforming government. It will also impose discipline going forward and reduce the cost of an eventual populist government.

In fact, our dollarization proposal contemplates a functional and financial restructuring of BCRA. Such restructuring requires cancelling all its liabilities by monetizing (not selling) all of its assets and other resources contributed by the National government. Conceptually, it is possible to dollarize if BCRA’s net worth is positive on a mark-to-market basis. As I will explain below, it is a mistake to assign a value of zero to BCRA’s financial assets under any scenario, but more particularly under dollarization with a credible fiscal adjustment plan.

Before proceeding with the analysis, several clarifications are necessary.

First, this is not an arcane technical issue. The BCRA is insolvent. Cancelling its financial debt is a necessary condition to eliminate inflation and channel more credit to the private sector (and also to dollarize). There are two types of solutions to this problem. One type involves a nominal and/or real haircuts on bank depositors and bank shareholders). The other type involves an orderly refinancing without any kind of haircut in the context of an adjustment that rapidly leads to a primary fiscal balance. Our proposal is of the second type. Dollarization offers tools that would be unavailable if the peso (or its successor) survives. Obviously it must be accompanied by a significant short term fiscal adjustment and long term fiscal sustainability. Dollarization provides the foundation for such regime change.

Second, the analysis that follows assumes the functional and financial restructuring of the BCRA (2).2 This would entail, among other things, a) creating a separate agency to supervise the banking system following global best practices, and b) relocating bank reserves outside of Argentina so that they can’t be used to finance the fiscal deficit.

Third, the analysis is not applicable to a going-concern scenario in which the BCRA and the peso survive under the current policy (3).3

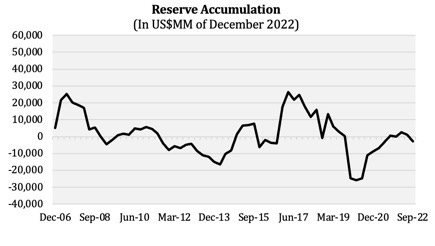

Fourth, it is conceptually wrong to extrapolate current circumstances to argue dollarization would not be feasible. Convertibility wouldn’t have been feasible in December 1989, but it was in March 1991. Although it is true that at the free exchange rate, today the BCRA does not have enough international reserves to “buy” the monetary base, it is impossible to know if this will be the case in 12 or 18 months. It is impossible to forecast the future. The lack of international reserves is not a structural limitation of the Argentine economy but a structural limitation of populist economic policies.

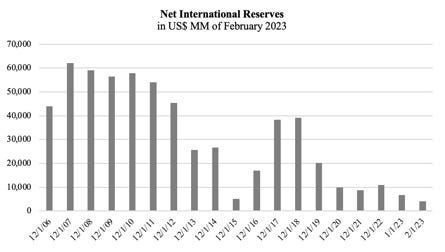

Going forward the change in international reserves will depend on a variety of factors such as the trade balance and foreign investment, which in turn will depend on the economic policy announced by the next government. In fact, as can be seen in the graph below, over the last 16 years BCRA was able to accumulate substantial reserves.

Fifth, we are not proposing dollarization today. We believe it as a solution to be considered by the next government. Even if the BCRA did not have enough international reserves, it would be possible to dollarize if the exchange rate that equalizes BCRA’s assets and liabilities is close to the free-market exchange rate. In other words, dollarization is possible if BCRA’s net worth on a marked-to-market basis is positive.

In practice, the conversion FX for dollarization is the maximum of a) the free exchange rate in a market without any government restrictions on foreign exchange transactions and capital movements (i.e., without the “cepo”), and b) the exchange rate that equalizes the assets and liabilities of the BCRA on a marked to market basis (the “break-even rate”). If the government were to dollarize at a below market exchange rate, there would be a significant risk of a bank run (people will not believe dollarization is viable and would convert their bank deposits into dollars). On the other hand, if the break-even rate exceeded the market exchange rate, at the latter BCRA would have all the financial resources it needed to dollarize.

Below are the key elements of our proposal to restructure BCRA in the context of a simultaneous fiscal adjustment program that rapidly leads to a primary equilibrium.

First, we need to simplify its balance sheet. Assets can be grouped into two accounts: net international reserves (NIR) and net domestic assets (which are mostly debt issued by national government). This last category includes: 1) Adelantos Transitorios (AT), promissory notes in pesos which mature in the next 12 months, 2) Letras Intransferibles (LI), which are non-transferable dollar denominated bills with maturities that extend up to 2033 and pay interest) and 3) a portfolio of government bonds. BCRA is simultaneously one of the main creditors of the national government and the largest debtor of the Argentine banking system (most of the bank deposits are currently used to finance the fiscal deficit).

BCRA's liabilities can also be grouped into two accounts: monetary liabilities which do not pay interest (peso bills and coins as well and non-remunerated bank reserves) and financial liabilities which pay interest (Leliq, Notaliq and the swaps).

Conceptually, we can split BCRA into two banks: 1) the monetary BCRA (BCRAM), and 2) the financial BCRA (BCRAF). In the BCRAM, NIR back monetary liabilities. By definition, it disappears with dollarization. In the BCRAF balance sheet, a portfolio of government debt is financed with onerous debt with the domestic banking system. With the current policy, the BCRAF’s is engaged in a massive negative carry trade (i.e., it funds a portfolio of non-interest-bearing assets with expensive peso debt). Until now it managed to pay negative real interest rates. It cannot do so indefinitely, particularly in a stabilization scenario. Sooner or later the danger of hyperinflation will put a stop to this policy.4

Knowingly or unknowingly, bank depositors are playing a game of musical chairs in which only half the chairs will be available when the music stops. There are several reasons for this anomaly. The cepo severely restricts the menu of available investment options for private savers (both individual and corporate).

On the other hand, measured in US dollars at the free-market exchange rate, total deposits in the banking system are at the same level as in mid 2006. This means only transactional money is deposited in the banking system. This means that the private sector needs them to operate and pay suppliers, wages and taxes. Since the largest peso note is worth less than US$5, the option of withdrawing cash from the banks must be discarded.

As mentioned earlier, many analysts incorrectly assume that the government debt held by the FBCRA is worth zero. What is the basis for such assumption? That these debt instruments are automatically “rolled over” at their stated maturity at the discretion of the Treasury. But assuming they are worthless ignores some basic financial concepts. First, with the same line of reasoning, one could argue that the BCRA's financial liabilities are also worthless since they are also automatically “rolled over” by the BCRA (as long as the interest rate it pays remains close to the inflation rate).

More importantly, if it were true that the FBCRA has no assets, there is no way for it to repay its liabilities, which in turn, the Argentine banking system is bankrupt. In other words, if the portfolio of AT, LI and other government debt securities held by FBCRA has no value, the Leliq and Notaliq are also worth zero and, therefore, bank and bank depositors stand to lose a substantial portion of their capital.

Under the assumption that there is a simultaneous fiscal adjustment, the first step in our proposal to restructure BCRA is to swap its portfolio of government bonds and bills for zero coupon bonds with the same ratio of present value to face value issued under NY law (with the 2038 indenture). The debt held by FBCRA is owed by the national government, which is at the same time its only shareholder. Therefore, the national government can unilaterally decide its capital structure (senior vs. junior, dollar vs. peso, etc.).5

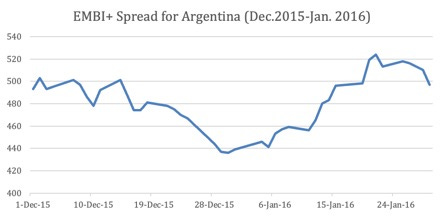

Nothing prevents the government from taking this step. In fact, there is a recent precedent. Between December 2015, the BCRA exchanged approximately US$16.1 billion in face value of LI maturing in 2016 and 2020 for a portfolio of dollar denominated government bonds maturing in 2022, 2025 and 2027. The authorities of the BCRA explained that with this swap they sought to “strengthen” the balance sheet. In fact, at market yields, the swap implied a capital contribution of almost US$1 billion.

The proposed swap would leave the gross and net debt of the national government unaltered. Therefore, it should not have any impact on country risk premiums. Once the swap is completed, it would be easy to calculate the present value of the swapped portfolio using the average current yield on Argentina’s outstanding dollar bonds.

The 2015 swap also refutes the notion that the proposed swap would depress the secondary market prices of Argentina’s bonds. Given that as of September 30, 2015, the face value of all of Argentina’s outstanding dollar bonds totaled approximately US$52.6 billion, the amount swapped represented a third of the total. Cursory examination of the data suggests the swap had no impact on secondary market prices. As can be seen in the graph below, Argentina’s EMBI+ spread fell in January 2015 although the market expected that the swapped bonds would be used in open market operations.6

In the context of our proposal to restructure BCRA, it would not make economic sense for the National Government to issue a dollar denominated debt security with an infinite yield to maturity (i.e., with a present value equal to zero) when its other dollar denominated bonds yield 25%. If the bonds have the same indenture, jurisdiction, collateral and subordination structure they should have the same yield to maturity.7 The "law of one price” inexorably applies, i.e., securities with the same risk must have the same expected return (in the case of a bond, this implies that they must have the same yield to maturity). Otherwise, there is an opportunity to make a riskless profit (unless there are legal impediments, which would not be applicable to the national government).8

At the end of February, Argentina’s dollar bonds issued under New York law yielded, on average, approximately 25% (4.1%, which is the 7-year US Treasury yield plus a country risk premium of 2090 basis points).

Again, there is no economic reason for a bond issued by the Argentine government to be worth 38 cents and another bond with the same issuer, average life, indenture, seniority, etc. to be worthless simply because it is held by the BCRA. If, due to market segmentation, structural subordination, collateral or any other reason, their price were different, the government could easily arbitrate it, especially since it controls the holder of the “junk” bonds (i.e., the BCRA). It would simply swap the bonds that are worthless for ones that are worth 38 cents (or their market price). In other words, the government can modify at will its own capital structure and the financial assets held by BCRA.

Moreover, if the automatic roll-over of AT and LI is the reason why they are supposedly worthless, this would be easily resolved with the proposed swap. After its completion, BCRA would hold a portfolio of bonds worth significantly more than zero.

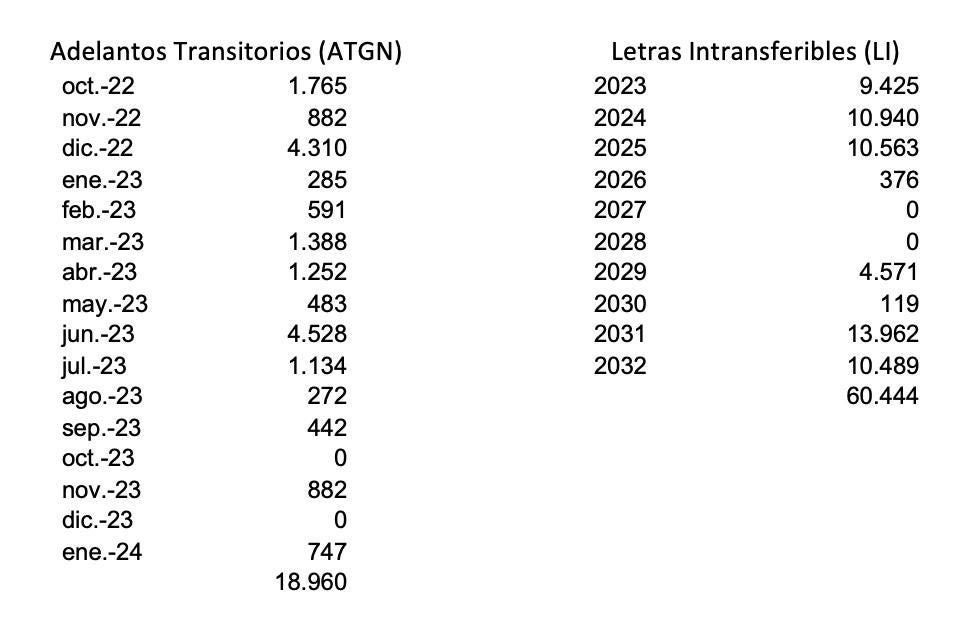

How can we calculate the market value of AT and LI? Their maturity schedule appears in BCRA’s audited financial statements. The latest available information is from December 31, 2021. But the Ministry of Economy publishes a quarterly debt report that provides details the amortization and interest payment schedule of the debt the national government owes BCRA. For example, as of September 30, 2022, the AT and LI this schedule was as follows:

Amortization Schedule (in millions of US$)

On that same date, in BCRA’s weekly balance sheet the peso denominated AT were valued at US$19,202 million while the dollar denominated LI at US$61,245 million.9 However, given the premium between the official and the market exchange rate, the “real” value of the AT was US$9,039 million.10 Consequently, as of September 30, 2022, the face value of the BCRA's financial assets amounted to approximately US$69,500 million.

Given that at that time the average yield to maturity of the NY law bonds maturing in 2029, 2030 and 2035 was 39.5%, we can estimate the present value of these assets at approximately US$26.800 million or 44% of their face value (significantly less than the liabilities of the FBCRA which amounted to US$28,500 million).

It is worth highlighting that given the duration of the swapped bonds, a reduction in the yield to maturity from 39,5% to 25% (the level as of February 15, 2023), would generate an increase in present value of almost US$6,000 MM or 30%.11

Someone could say that if the BCRA sold the swapped bonds in the secondary market under a liquidation scenario, their price would fall (ergo, their yield would increase), therefore these estimates are not realistic. This argument could be theoretically valid if the idea was to sell the swapped bonds in the secondary market. But even under this scenario, the face value of the swapped bonds would be less than 40% of the US$172 billion in face value of all Argentina’s outstanding dollar bonds. Even if we contemplated selling these bonds it is impossible to justify the assumption that they would worthless.

However, as we explained in Dolarización: Una Solución para la Argentina, this is precisely the opposite of what we propose. Monetizing is not the same as selling. The distinction is key. More on this later.

The proposed swap, however, is not innocuous from the point of view of the Treasury, because it will no longer be able to automatically roll over the debt it owes to the BCRA (i.e., extend maturities at will), and therefore, it will have to disburse cash to pay interest and capital.

It would be irresponsible to suggest (as some analysts do) that the BCRA should not pay its debt to the banking system (and therefore to depositors). Under the current scheme, certain "geniuses" who aspire to occupy the Ministry of Economy in the next government believe that they can solve the Leliq problem with a combination of “real haircuts” via inflation and “nominal haircuts” via some type of reperfilamiento (euphemism for a restructuring). If this is the case, they should openly say that their plan is to confiscate private savings deposited in the domestic banking system.

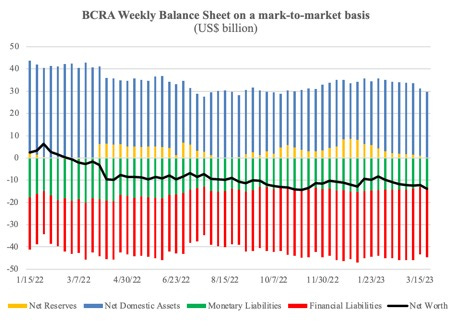

Back to our proposal, having first swapped the AT and the LI for zero coupon bonds issued under NY law, we can restate the balance sheet of the BCRA on a mark-to-market basis. A very different picture emerges from the one gets by looking at weekly balance sheet published by the BCRA. The following graph shows the condensed mark to market balance sheet of BCRA since December 2021. As can be seen, during most of the year, its net worth was negative, i.e., the central bank was insolvent. However, it is important to highlight that this result reflects the current economic policy. A credible regime change would lower country risk spreads and increase the value of the bonds held by the BCRA.

In a scenario of dollarization, BCRA’s net worth depends on two variables: the conversion exchange rate and Argentina’s country risk premium.12

A devaluation of the peso improves BCRA’s net worth because its assets are mostly denominated in dollars and its liabilities in pesos. On the other hand, a rise in Argentina’s country risk premium (or nominal US interest rates) has the opposite effect since it reduces the present value of its bond portfolio.

The announcement of a dollarization regime and a program of structural reforms (a permanent reduction of public spending and taxes, deregulation, labor flexibility, opening of the economy, etc.) by a new government with a strong electoral mandate, will likely lead to lower country risk premiums. Dollarization alone does not make sense. It only makes sense as a commitment device that can reduce time inconsistency.

By how much can the country risk premiums fall? Under a conservative scenario and assuming dollarization and a credible path to fiscal balance are announced by the new government, we can assume it would fall to the average for the period January 2008-January 2023, approximately 1050 basic points. Given that the 5-year rate US Treasury benchmark currently yields 4.5%, the appropriate discount rate to value BCRA’s balance sheet in a liquidation scenario would be approximately 15%.

Given the duration of BCRA’s bond portfolio, a drop of almost twenty percentage points in the yield to maturity would generate an increase of almost 60% in its present value. As result its net worth would turn positive at US$1.7 billion (an unrealized gain of almost US$11 billion for its sole shareholder, the national government). With the passage of time, as the government gains credibility, country risk premiums will continue to fall leading to further gains in the value of this portfolio.

However, any solution that contemplates selling BCRA’s bond portfolio at a price equivalent to a 15% yield would be sub-optimal. To begin with, as I already pointed out, it would tend to depress prices in the short term (i.e., increase the yield to maturity). More importantly, why sell an asset whose market value is 40% of face value, if thanks to the announced regime change in a relatively short time it could be worth 60% or 70% of face value?

The optimal solution involves some financial engineering that is commonly used in the US capital markets by private borrowers. There are several securitization structures that can achieve the objective of monetizing FBCRA’s assets without selling them.

One of the many advantages of dollarization for countries like Argentina is that it opens the doors to the largest and most liquid capital market in the world. The structure we propose below would allow the national government to “capture” a large part of the upside generated by its own policies. In other words, it would not leave “money on the table”. It is not the same to access the dollar capital markets when the dollar is the country’s legal tender than when the peso survives. In the latter case, there is always a risk of devaluation which given the currency mismatch of the private and public sector can lead to financial and macroeconomic instability.

Our proposal implies a functional and financial restructuring of the BCRA, which, very briefly, would require:

1) Contributing its financial assets (a portfolio bonds swapped for AT and LI) and financial liabilities (Leliq, Notaliq, etc.) to a special purpose vehicle -the Fondo de Estabilizacion Monetaria (FEM)– established outside of Argentina.

2) The government would contribute additional financial resources to reinforce FEM’s collateral (the assets would include the liquid bond and equity portfolio held by the FGS worth US$25 billion, any proceeds from the sale of the 5G spectrum, the government’s stake in YPF (without political rights and with a right of first offer at market value), 20% of the tax revenues generated by agricultural exports), and any other asset or revenue that is not sovereign risk. After these contributions the face value of FEM’s assets would be close to US$100 billion. The residual beneficiary of the FEM would be the National Government and/or the BCRA and the FGS.

3) Negotiate a credit enhancement with multilaterals in the form of a first-loss guarantee (for example, the first 30 cents in the event of default). This facility does not necessarily need to be disbursed. It is contingent, the more credible the program the less likely that disbursement will occur. Obviously, this is not going to be an easy negotiation. Argentina has exhausted its credibility. On the other hand, as Keynes said “if you owe your bank manager a thousand pounds, you are at his mercy. If you owe him a million pounds, he is at your mercy.” The reality is that Argentina will need external support to extricate herself from a bad equilibrium, itself a consequence of years of policy mistakes.

4) Negotiate a backstop underwriting facility with a group of international banks that would act as dealers of FEM’s asset backed commercial paper (ABCP) program.

Under this scheme, there would be no increase in public debt. In addition, any debt issued by FEM would be non-recourse. Basically, this structure allows for an efficient recapitalization of the BCRA and an orderly refinancing of its debt to the Argentine banking system without any haircut.

An excess of collateral (2 : 1 at market values at t=0) and the credit enhancement are critical because Argentina is a serial defaulter and has no credibility with investors or the international financial community.

Without these two features, FEM would not be credible on the first day (its funding cost would be very high). Besides, given its asset-liability maturity mismatch it would find it impossible to cancel the latter without causing a collapse in the secondary market for Argentine debt.

To repay the debt inherited from FBCRA, FEM would issue collateralized commercial paper (ABCP) at market rates. Therefore, there would be no haircut for banks or depositors. The market interest rate for FEM’s commercial paper would be lower than the yield for Argentine bonds for two reasons: a) credit enhancement and b) excess collateral. In addition, all debt issued by FEM would have a maturity of less than one year, and therefore its holders would reflect it in their balance sheet as a current asset.

With the cash flow generated by the assets inherited from the BCRA and the additional resources contributed by the government, we estimate that within four years FEM could repay 100% of the inherited debt, which today at the CCL amounts to approximately US$30,000 million, and its own ABCP plus interest. Once the last cent of that debt is repaid, FEM would cease to exist and any remaining government bonds in its portfolio would be automatically cancelled, generating the largest reduction in public debt in Argentine history (without a default).13

Swapping the portfolio AT, LI and bonares for a portfolio of bonds issued under NY law could with the same ratio of PV/FV would give the Treasury a two-year grace period to compensate for losing the "roll over" option. There are N possible ways to build a portfolio of zero-coupon bonds with the same PV/FV ratio as AT and LI. The table below shows four possible ways to extend the average life of the LI.

The proposed financial engineering would make it possible to refinance BCRA’s financial debt in an orderly manner without a nominal or real haircut to depositors or Argentine banks.

With dollarization and ongoing structural reforms, the economy would grow strongly, as was the case after the launch of Convertibility in 1991. The risk of devaluation and the currency mismatch in the public and private sectors would immediately disappear. The country would once again be able to access the capital markets to refinance its existing debt and avoid default.

The financial liabilities of the BCRA hang like Damocles’ sword over the banking system and the Argentine economy. This is undoubtedly one of the most serious challenges facing any stabilization plan. If we look at history, the theory that we can easily repay Leliq with an increase in the demand for money seems illusory. If we want domestic savings to play a role in financing the development of the Argentine economy, any solution to the “Leliq problem” must avoid confiscating private sector savings in real or nominal terms or damage the banking system. We believe dollarization provides the best tools to accomplish this objective if accompanied by a strong fiscal adjustment (lower permanent public spending). One does not make sense without the other. However, the latter will not be politically feasible without eradicating inflation quickly. In the current scenario is the least risky alternative to accomplish this goal would be dollarization.

Footnotes

The political feasibility of dollarization will depend fundamentally on the state of the economy. The three important monetary reforms since 1983 –Austral, Plan Bonex and Convertibility– were announced when the monthly inflation rate exceeded 10% (more than 20% in the first two cases). Congress will vote in favor of dollarization to escape hyperinflation.

There are multiple ways to dollarize and restructure the central bank. Our proposal is one of N possible variants. Which variant is the optimal one shall depend on the particular circumstances at the time a government decides to dollarize.

The current situation is not sustainable. With or without the peso, a restructuring of Leliq (i.e., a recapitalization of the central bank) is a necessary condition to eliminate inflation.

The central banks of the advanced economies are beginning to face a problem that in certain aspects resembles the one BCRA faces, i.e., a quasi fiscal deficit. In the case of the Fed, QE consisted of buying medium and long-term treasury securities and MBSs with remunerated reserves under the so-called floor system. As the rate of the latter fell below the yield of the former, it was a positive carry trade. But with the rise of inflation, short-term nominal interest rates have risen, and the situation reversed leading to realized and unrealized losses.

The argument that the AT and the LI are subordinated debt (junior) that are riskier than the bonds issued under NY law and therefore pay a higher interest rate (although less than infinite) may be valid while the BCRA and the “cepo” exist. We know from the Miller-Modigliani theorem that the liability structure with which an asset is financed does not alter the present value of future cash flows. It is for the government to decide with which capital structure (debt) it wants to fund itself. Although the AT and LIs should be discounted at a higher rate today, with dollarization and the proposed swap they would become senior debt and, therefore, would have the same yield as the NY law bonds. But in a scenario of liquidation of the BCRA with dollarization, it would be appropriate to discount their expected flows at the same YTM.

Obviously other factors played a role as well. But in a context of improving long term debt sustainability, it is difficult to suggest, from an empirical and theoretical point of view, a deterioration in prices because of the proposed swap, especially since the bonds are not going to be sold in the secondary market. The argument would make more sense if the AT and LI were swapped for new series of outstanding bonds, for example, a portfolio of 2029, 2030 and 2035. But the bonds issued in the proposed swap would be zero coupon bonds that do not exist today.

There are significant differences between the YTM of bonds issued under NY law that mature in 2030 and 2038 due to the difference in their indentures.

AT and LI do not meet the legal or economic definition of the term “securities”. In fact, LI are non-transferable. But the government can change their legal status.

The difference between the figures published the BCRA and the quarterly report published the Ministry of Finance is probably the present value of the interest to accrue for the Non-transferable Bills whose total value at that date was US$1,345 million.

It would not be correct to divide the value in pesos of the LI as it appears in official statistics by the free-market exchange rate since these instruments are denominated in dollars.

Some analyst value LI at 20% of their face value, which implies an IRR of 66%, which unjustifiable given current country risk premiums. While this assumption is valid in a default scenario it would not be applicable under a scenario of dollarization with fiscal adjustment.

The new zero-coupon bonds would be issued under 2038 indenture.

The National Government would be the sole beneficiary of the FEM, which at the same time would become its largest creditor. If, once the FEM debt is paid, its residual portfolio of government bonds would be automatically canceled. As a result, gross debt would converge to net debt. Alternatively, both BCRA and FGS could be added as beneficiaries. Legal considerations will determine which option is preferable.