Krugman is wrong on Argentina, again

Paul Krugman has a history of making the wrong policy recommendations for Argentina. He now opposes dollarization. Another reason to move forward with it.

Krugman is at it again. This time arguing in his NYT’s column that the case for dollarizing Argentina requires a belief in magical thinking. On the contrary, it is Krugman’s views and policy prescriptions that are closer to a dangerous thaumaturgy. When it comes to Argentina’s economic policy, shooting from the hip has become a Krugman tradition. A very superficial knowledge of the country’s history and its problems, has led him to consistently advocate and celebrate misguided policies that had disastrous results.

At the end of the 1990s, Krugman was among a group of US economists who promoted the view that the solution to Argentina’s troubles was exiting the Convertibility Plan through “an orderly devaluation.” After the crisis of 2002, he cheered the ficticious and unstustainable recovery promoted by the Kirchner’s populist policies. If anything his current opposition to dollarization is a positive indicator. Krugman has been consistently wrong for the last three decades.

In January 1999 Brazil devalued its currency. The impact was immediately felt in Argentina. President Menem was quick to react and announced that his government was considering full dollarization. His economic team had been working with the US Treasury on the idea since the Thailand crisis of 1997. However, the project floundered due to internal (presidential elections in Argentina) and external factors (the unwillingness of the US government to compensate Argentina for lost seignorage).

In July 1999, Krugman argued in Slate that “the serious lesson” to be drawn from Argentina’s economic travails was a strong refutation of the notion “that a credibly stable currency is all you need to promote prosperity.”

The problem, you see, is that the same rules that prevent Argentina from printing money for bad reasons –to pay for populist schemes or foolish wars– also prevent it from printing money for good reasons such as fighting recessions or rescuing the financial system.

Krugman’s conclusion derived from an erroneous diagnosis of the situation. Argentina’s presidential election in late 1999 confronted two candidates: Fernando De la Rua, who led a center-left coalition, and Eduardo Duhalde, the leader of the incumbent Peronist party. Convertibility was the decisive issue. Duhalde publicly voiced his opposition to the currency regime and advocated a sovereign debt restructuring. With memories of hyperinflation still fresh in their mind, voters took notice. De la Rua won. Ironically, Duhalde belonged to the same political party as Menem, who in 1991 had championed the hard peg with the dollar.

By the time De la Rua assumed the presidency on 10 December 1999 the economy was recovering strongly. Exports, industrial production and construction activity were at or above the levels of 1997. In fact, as can be seen it the graph below, industrial production recovered faster than after the Tequila crisis that started in December 1994.

However, the first announcement of the new government was a tax hike that undermined business confidence and aborted the recovery. To make matters worse, the commitment of the De la Rua’s administration to maintaining the peg to the dollar started to show fissures. Ten months into the new administration, former president Raul Alfonsin, publicly stated that Convertibility and the military coup of 1930 were the two worst things that had happened to Argentina in the 20th Century. On prime time TV he described the currency regime as “a deadly trap.” As pointed out by Corrales (2002), until the last days of the De la Rúa administration, “the most relentless critic of the government’s economic policy was the ruling coalition itself.” Rudi Dornbusch, who visited Buenos Aires at the time, publicly suggested that one of the most important measures the government could take was to get Alfonsin “to shut up.” Substantial damage was done and the aborted recovery turned into a deep recession.

The negative effect of Alfonsin’s pronouncements was compounded by the resignation of the Vice President in November 2000 in the midst of a political crisis. A weakened administration presaged the end of Convertibility. It was a turning point. Deposits started to flow out of the banking system and country risk premiums started to creep up. Brazil’s devaluation of the real didn’t kill Convertibility, politics did (more specifically, Alfonsin y Duhalde did with some unwitting help from the IMF and the Bush administration).

By mid 2001, some conservative economists such as Allan Meltzer advocated a sovereign default. In November 2001, as the crisis was reaching its climax, Krugman argued that a sovereign default would “do nothing to end the economic crisis.” The way out of Argentina’s problem was an “orderly devaluation” of the peso, i.e., an exit from Convertibility. “It's hard to believe that Argentina will sacrifice not just its economy but its credit rating on the altar of a discredited monetary theology,” Krugman wrote. “But as you read this, Argentine officials are crucifying their long-suffering nation on a cross of dollars.”

In 2002, the Duhalde government followed the recommendations of Krugman, Stiglitz and others. However, since the banking system was mostly dollarized there was no orderly way of “breaking” the peg between the peso and the dollar. Confiscating people’s savings destroyed trust in government and the country’s institutional fabric. Many devaluationists were surprised, since they had expected a strong economic recovery. As Dallas Fed economist Carlos Zarazaga pointed out in a 2003 article, “the devaluation cure was worse than the disease.”

It appears that Alfonsín, Duhalde and the many economists, businessmen and politicians who supported them, underestimated the consequences of devaluing the peso. In his first press conference, Duhalde’s Economy Minister Jorge Remes Lenicov, stated that the planned devaluation of the peso would have “a reactivating effect” on the economy (La Nación, 2002). In fact, as pointed out by Edwards (2002), the minister “remembered that in 1967 a 40 per cent devaluation had been highly successful; it did not generate inflation and the value of the peso stabilised rapidly.” Two months later, public officials at the Ministry of Economy “reaffirmed their confidence” that the drop in GDP would “not be greater” than 4.9%. Remes Lenicov resigned a month later. His estimates turned out to be widely off the mark: during 2002 GDP fell by a staggering 11% (higher than in 1930) and the poverty rate exceeded 50%, setting historical highs. What saved Argentina from an economic and social catastrophe was a very fortunate and very strong reversal of a decades’ long decline in agricultural commodity prices, that was driven by China’s rapid industrialization.

Krugman remained oblivious to all these considerations and defended Duhalde’s devaluation of the peso. He then went on to cheer the Kirchner’s unsustainable fiscal expansion. He publicly lauded Argentina’s recovery as “extraordinary,” and lamented that Argentina media didn’t concur with this assessment.

On May 5, 2004, Argentine president Néstor Kirchner and Krugman held a conversation about Argentina’s economic predicament.

The first thing is just to say, obviously, congratulations on the performance. Argentina had a worse crisis even than I had imagined. I think I may have been one of the first to say that convertibility was not going to survive. I said that convertibility would not survive the decade, and I was off by one year. But it did end, and it ended with a catastrophic crisis, which was worse than anything we had imagined. And recovery now is much more rapid than anything we had imagined, and that is a very good thing. It’s a combination of probably hidden strengths in the Argentine economy that we did not realize, and policy, which has been good… it never made sense to have [the peso] pegged to the dollar.

In his “The Return of Depression Economics” published shortly after Lehman’s collapse, Krguman devoted a few paragraphs to Argentina’s experience with Convertibility. He reiterated his view that the country had “made a strong recovery” since 2002 thanks to the devaluation of the peso and “a settlement in which the government paid only about thirty cents on the dollar of its foreign debt.”

However, Krugman’s optimism was misplaced. According to official statistics available at the time, Argentina’s GDP per employed person grew 23% between 2002 and 2005. But this performance was far from impressive. However, in 2006, using a model calibrated for the Argentine economy, Dallas Fed economist Carlos Zarázaga showed that GDP per employed person should have grown by about 35% during this period.

In early 2010, Krugman began his campaign for breaking up the Eurozone. Echoing his November 2001 column on Argentina, he argued that a sovereign debt restructuring wouldn’t help Greece “all that much.” What the ailing European country needed was a devaluation of its currency. Krugman’s campaign in favor of a Grexit continued and soon included Portugal, Ireland and Spain. In a blog post dated January 2011 he drew a comparison between Greece and Argentina

Some economists, myself included, look at Europe’s woes and have the feeling that we’ve seen this movie before, a decade ago on another continent — specifically, in Argentina. [...] Argentina didn’t simply default on its foreign debt; it also abandoned its link to the dollar, allowing the peso’s value to fall by more than two-thirds. And this devaluation worked: from 2003 onward, Argentina experienced a rapid export-led economic rebound.

A few months later he praised a column by Matt Yglesias, who lauded Argentina’s recovery following its exit from the Convertibility and recommended Spain should follow the same path. “As he says,” wrote Krugman, Argentina’s is “a remarkable success story, one that arguably holds lessons for the Eurozone.” In a post dated October 24, 2011 he complained about the “remarkable unwillingness” of the media “to face up to the reality that Argentina has done very well since its default and devaluation.” Krugman joined Stiglitz in the pantheon of international apologists of the economic policies of the Kirchner regime. His pronouncements were celebrated by Cristina Kirchner, who even quoted Krugman in defense of her track record.

Krugman’s cheerleading of the Kirchner’s economic model generated a response from several economists inside and outside Argentina. Ivan Carrino pointed out the inconsistent positions that Krugman had taken over time. Adrian Ravier explained why Krugman was wrong in his assessment of the 2002 crisis and the recovery that ensued. First, he had underestimated the negative social, economic and institutional impact of the 2002 crisis. Second, he had overestimated the extraordinary “growth” of Argentina's economy between 2003 and 2011. To be fair, the latter was not entirely Krugman’s fault. Starting in 2007, the Kirchner administration started tampering with official macroeconomic statistics. According to Ariel Coremberg this manipulation led to a 50% overestimation of the annual rate of growth of GDP between 2006 and 2012.

Krugman would have done well to read the classic study of populism in Latin America by Dornbusch and Edwards (1991). Under populist regimes, policymakers typically embrace economic programs “that rely heavily on the use of expansive fiscal and credit policies and overvalued currency to accelerate growth and redistribute income.” Such policies, they explained, “have almost unavoidably resulted in major macroeconomic crises that have ended up hurting the poorer segments of society.” This is exactly what happened in Argentina during the Kirchner’s years.

Its 2023 and Krugman is wrong again. Clearly dollarization cannot do magic. But believing that Argentine policymakers will use monetary policy to do “the right thing” is magical realism. In fact, the historical record shows they have used it to do the wrong thing. That is why the average annual inflation rate since 1945 exceeds 60%. As Rudi Dornbusch pointed out decades ago, in countries like Argentina “exchange rates have been the dominant instrument of destabilization.”

When it comes to Argentina and dollarization, Krugman and many economists fall into the Nirvana fallacy. Comparing dollarization with a regime in which an independent and competent central bank follows optimal intervention rules is nonsense, as such regime has zero chances of ever existing in Argentina. John Cochrane explained it very clearly in a recent post":

“The lure of technocratic stabilization policy in the face of Argentina's fiscal and monetary chaos is like fantasizing whether you want the tan or black leather on your new Porsche while you're on the bus to Carmax to see if you can afford a 10-year old Toyota.”

Devaluing the peso has not and will not increase Argentina’s competitiveness. As can be seen in the graph below, despite a decline in prices, during the Convertibility plan with a hard dollar peg, export volumes grew much faster than after the massive devaluation of the peso.

There is another cost that devaluationists of all stripes tend to ignore: the volatility of real exchange rates, which as Mundell always emphasized, “aggravates instability of the financial markets, disrupts trade and the efficiency of capital flows.” Moreover, any FX regime with recurrent devaluations (like the one prevailing in Argentina since 2002) imposes a higher cost of capital on the economy and lower equilibrium real wages.

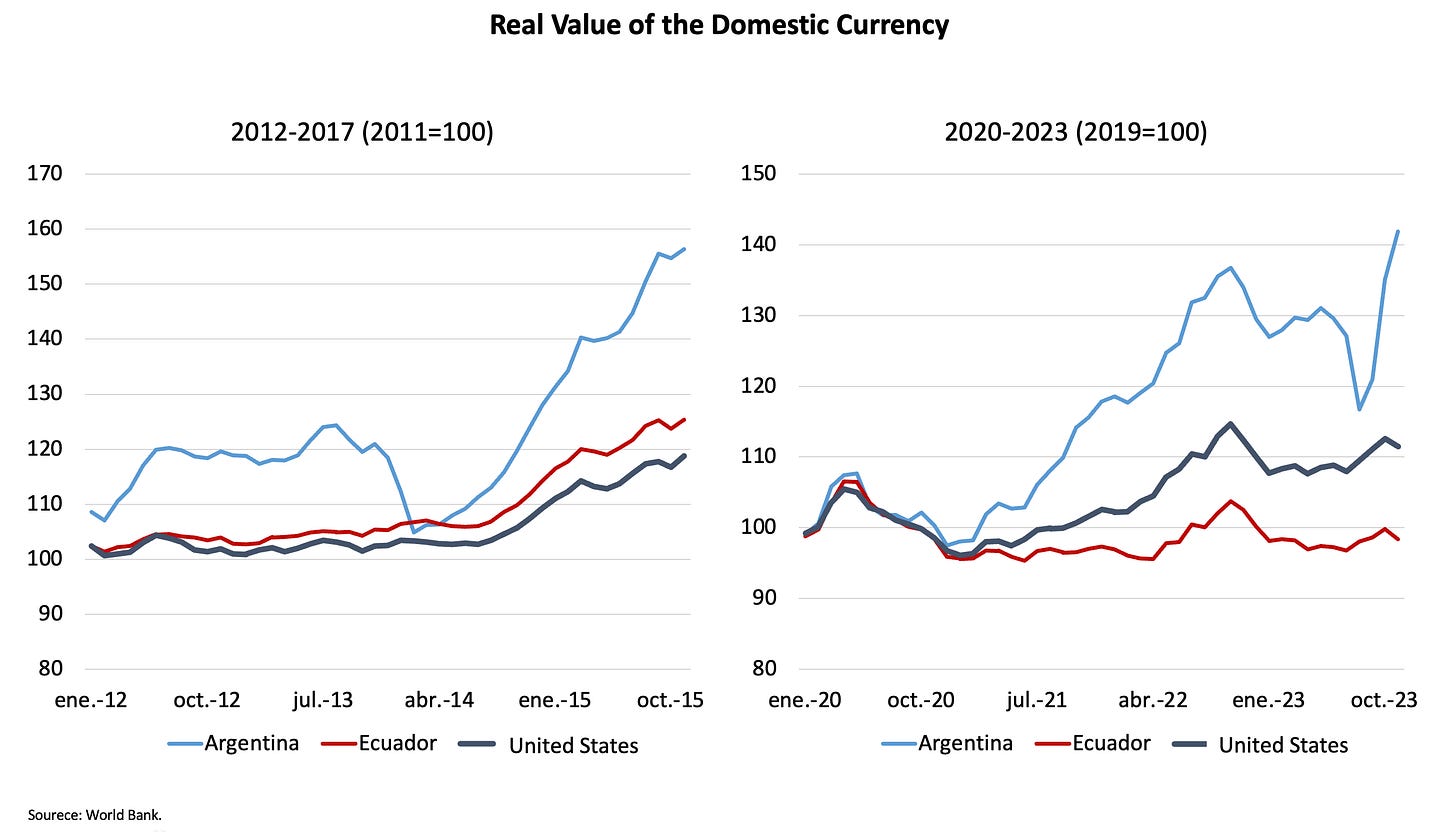

Krugman also seems to ignore that the much-maligned appreciation of the peso that took place under Convertibility was less intense than during the many versions of Kirchnerismo. In fact, the last version under Alberto Fernandez generated in less than four years almost as much real appreciation as ten years of a currency board.

There are no surprises here. It is an historical fact that seems to escape Krugman. Under populism, which since 1945 has been endemic in Argentina, the peso behaved even more pro-cyclically than if the economy had been dollarized. This can be seen comparing the behavior of real exchange rates in Argentina and Ecuador during the last two cycles of global appreciation of the dollar.1

What Krugman also doesn’t seem to understand is that Argentines have not only already dollarized their savings but also a substantial part of their liquidity. The amount of dollar bills circulating in Argentina, stashed under the mattress or kept on safety deposit boxes is five times greater than peso denominated M3. This is not a new state of affairs. When novelist V.S. Naipaul visited Argentina in 1973 he was surprised. “Salaries, prices, the exchange rate: everyone talks money, everyone who can afford it buys dollars on the black market. And soon even the visitor is touched by the hysteria,” he wrote. Not surprisingly, it was around this time, June 1973, that Milton Friedman explicitly advocated dollarization as an option for Argentina:

There are no gyrations in American monetary policy which can hold a candle to the gyrations which have occurred in Argentinian domestic monetary policy. So, the whole reason why tying to a major currency would be an advantage to Argentina is that precisely that it would prevent them from following bad domestic monetary policies. They would have less of an adjustment problem simply because our policy will prove to be more stable than theirs.

As I have written elsewhere, in this regard nothing has changed in Argentina. Inflation is rampant (analysts expect a monthly rate of 30% for December). At some level, the discussion of whether Argentina should dollarize is absurd. The dollar is not only a unit of account and a store of value for most Argentines but also a medium of exchange in real estate, private medicine and other transactions. There is no long-term financing in pesos for the public or private sector. More than half of the national government’s is denominated in dollars. At current exchange rates the monetary base is equivalent to one months of exports.

A large number of people in Argentina have already chosen the dollar as a currency to protect their purchasing power in the face of rampant inflation. There is only one segment of the population that cannot do this: salaried workers and retirees who barely make ends meet. They are the ones who suffer the most from this state of affairs. Dollarization would be an equal opportunity policy. If you have doubts about it, take a trip to Ecuador and ask people on the street what they think about having their economy dollarized.

The transaction costs involved in buying dollars to protect one’s purchasing power to sell them later to pay for expenditures are significant. Assuming that a hundred billion in dollar bills exchange hands every year, the bid-ask spread would amount to roughly 0.5% of GDP. Giving the dollar legal tender status would eliminate this cost immediately.

Not dollarizing now would be a big mistake. Obviously, in current circumstances it would only be possible with external support. But such support would only be transitory. As the experience of Ecuador shows, a successful dollarization is self-financing.2 It basically requires people to again deposit their savings in the banking system. Most other objections to dollarization can be easily dismissed.

Also, as Scott Sumner has pointed out, the dollar is currently at historically high levels. In fact, it is 40% stronger than it was in April 1991, when Convertibility was launched. Today a depreciation of the dollar in the coming years seems more likely than an appreciation (the opposite of what happened during the nineties).

Dollarization cannot do magic. What it can do very effectively is eliminate inflation rapidly. This is a necessary (not a sufficient) condition for structural reforms to survive and succeed. There is only one issue that a majority of Argentine voters care about independently of their ideology: eliminating inflation. The reason is obvious: most people live on a fixed salary that is paid once a month and adjusted slowly. Double digit monthly inflation rates are a heavy tax on the poorest segments of society.They are the ones would benefit most if the government adopted the dollar as legal tender.

Structural reforms are essential to put Argentina on a sustainable growth path. But failure to bring inflation down rapidly will put an end to any reform effort. Not due to economics but politics.

Having some form of external support is not a pre-condition for dollarization. The only reason it is advisable in current circumstances to have some transitory backup financial support is to eliminate the risk of a run on bank deposits. Net international reserves at the central bank are negative and the central bank is the largest debtor of the domestic banking system.