This paper contains Part III of my book Playing Monopoly with the Devil: Dollarization and Local Currencies in Developing Countries, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006, pp. 195-234.

The conventional optimal currency area theory

What are the implications of the analysis of the previous parts of the book for the fundamental question about the choice of a currency regime: should a country have a currency of its own or adopt an international one? This question is the subject of this part, the last of the book.

This question is routinely dealt with the criteria established by the optimal currency area theory. According to these criteria, a country should have a currency of its own if it meets the following conditions:

Given all the facts that we have analyzed in the previous parts of the book, we can ask ourselves how optimal the optimality of the conventional optimal currency area theory is.

A cursory review shows that it has at least four grave faults. First, it focuses the optimality on the features of geographical regions, not on the services that a currency should provide in such regions to turn them into optimal ones. It does so because it assumes that the optimality is given by the possibility of manipulating the currency and not by the quality of the currency itself. Second, it assumes that local currencies will react to manipulations in ways we know are unrealistic in developing countries. Third, it focuses on trade, ignoring the financial dimensions of the choice of currency. For this reason, its application results in grave conflicts between the financial and trade aspects of the choice of currency. Fourth, the theory ignores the preferences of the populations and because of this spontaneous dollarization is overtaking it.

I develop these points in this part of the book. I analyze the main faults of the theory in this chapter. Then, in the next one I propose a different set of criteria to define an optimal currency area, based not on the features of economic regions but on the services that the currency should provide to be considered optimal. Then I summarize the conclusions of our analysis in the last chapter of the book.

By defining optimality on the features of geographical regions exclusively, assuming that any currency would be optimal when the conditions enumerated above hold, the theory leaves aside all the essential qualities that turn a currency into real money. As we discussed in chapter I, there are two dimensions to the role of money, one fundamental and the other accessory. The fundamental one is that it must establish a standard of value. The accessory one is that, once it has attained that objective, it can be used to manipulate economic behavior in desirable ways. Money cannot play the second role without first having met the first one. Focusing only on the second leaves the theory not just incomplete but also misleading. Practically all countries in the world meet the conditions to be optimal currency areas according to the theory. They also manipulate their currencies, the ultimate objective of the theory. Yet, it is difficult to consider as optimal currency areas where inflation rates are as high as those that have been common in developing countries; where interest rates are high and financial intermediation low; where the danger of deadly currency crises is always present; where people cannot plan ahead because the value of the currency is always dropping; and from which people escape as soon as they see an opportunity to do it. It could be argued that the theory assumes that these problems would not exist. But, if the theory would not classify these cases as optimal, it does not say so explicitly and it does not contain any recommendation regarding a second best when all the conditions set above were fulfilled but the currency itself would not meet the conditions established by people to consider it as real money.

In part, these problems arise because of the second flaw of the theory: it assumes that currencies in developing countries would react to manipulation in an optimal way. The experience in the developing countries shows that such assumption is unwarranted. The ability to devalue the currency has failed to spur exports growth in the long term and actually the countries that devalue the less are the ones that have experienced higher rates of growth of both exports and general economic activity. Different from developed countries, the strategy of expanding monetary creation to spur economic growth backfires, as the devaluation results in increases in the rates of interest. As central banks have pursued this strategy even if it backfires, the rates of interest in developing countries tend to be higher than in the international markets. Additionally, financial intermediation is weak. Furthermore, local currencies have been at the center of the grave financial crises that have afflicted many of these countries. Typically, the origin of these is the mismanagement of monetary policies before the crises, which then leads to currency runs, which in turn lead to financial crises. Then, the currency runs have gravely complicated the solution of the crises. The promise to afford a lender of last result has also proven hollow, as central banks cannot resolve currency runs without losing dollar reserves, which turn their effectiveness contingent on getting dollars from the IMF, the other official international financial institutions and the markets. Finally, local currencies have become an obstacle for the integration of their countries to the international financial markets and the benefits of financial globalization.

Of course, these problems affect developing countries in different degrees. Many of these countries apply prudent monetary and exchange rate policies. As we saw in the Figures in part I, these countries tend to have lower interest rates and to be more successful in terms of exports and overall economic growth. But the previous paragraph describes the general situation of developing countries.

In fact, all these problems arise from the inability of the local currencies to establish themselves as standards of value—precisely the dimension of the roles of money that the theory ignores. It can be argued that this problem is particular to the circumstances of developing countries, including their tendency to fiscal irresponsibility. A theory that leaves out sets of circumstances that are common in the real world, however, is at best incomplete.

By exclusively focusing on the trade aspects of the choice of currency, the theory compounds these problems. As we saw in part I, local currencies have failed to deliver their promises on the trade area. At the same time, currency areas that are considered optimal in accordance with the conventional theory face serious foreign exchange risks on their financial operations. These risks have turned into grave currency and financial runs with devastating consequences for the optimally created currency areas. Ignoring the financial side of the currency areas has posed a serious challenge to the internal logic of the theory. These crises have generated the “fear of floating”, which denies developing countries the supposed benefits of having created their own optimal currency area. Countries wanting to keep their own currency have two options to deal with such fear. The first is to surrender to it, adopting a fixed exchange regime and, through this, surrendering their power to manipulate their monetary variables. According to the theory, this would nullify the optimality of their currency area. More precisely, they would not be using the potential optimality of their already optimal area. The other choice is to severe as much as possible their financial links with the rest of the world—thus renouncing to all the benefits of financial globalization. That is, to remain optimal, a currency area must forgo those benefits. A theory that defines as optimal a currency area that confronts such a hard choice cannot be right.

In fact, we can doubt that a theory that does not take into consideration the preferences of the people could define what is optimal. Spontaneous dollarization shows that these preferences may diverge markedly from what the theory dictates. Through their choosing of international currencies to denominate their domestic financial operations, people are creating currency areas that are, by the definition of the word in plain English, optimal for them. They choose the foreign currencies precisely because they allow them to escape from the local traps that the theory regards as optimal.

Spontaneous dollarization is a manifestation of the old Grisham’s law. This law is frequently stated as asserting that bad money drives out good money from circulation. The rationale for this statement is that when a government forces debased money on people while a good currency is also available, people prefer to spend the bad money and save the good one. Grisham stated the law in times when governments issued coins that mixed baser metals with gold, pricing them at the same value as the previously issued ones that contained only gold. Grisham observed that the good coins disappeared from circulation, as people wanted to rid themselves of the debased ones while saving the good ones. Shifting the perspective of the analysis, the law can be stated in a reversed way, saying that good money always drives out bad money as a standard of value and as the currency for saving and contracts. This is the process through which spontaneous dollarization has advanced throughout the developing world. This is the process through which optimal currency areas expand, driven by the choices of the people. Of course, the advantages of a currency increase with the number of users. By its own nature, money has enormous economies of scale in all the roles that it plays in society, so that the larger the number of people using it, the better the currency becomes for all the users. In this way, a desirable currency generates a virtuous circle, offering increasing benefits for its adoption.

Looking at the conventional theory from the point of view of Grisham’s law, we can summarize its shortcoming. By failing to recognize that currency is the fundamental word in the expression optimal currency area, the conventional theory fails to see that it is the quality of the currency, not the features of a region, what creates an optimal currency area.

This poses a crucial question: an optimal currency area should be optimal for whom?

There is no question that the possibility of manipulating local currencies affords tremendous power to both local and international monetary authorities. Ostensibly, these functionaries act on behalf of the people. Yet, the fact that people try to escape from their power suggests that monetary management has generated a classical instance of the principal-agent problem. By ignoring people’s preferences and focusing on maximizing the ability to manipulate the currencies, the optimal currency area theory supports the case of the agents (those who manipulate currencies) against that of the principals (the people).

The theory has other important shortcomings that plague it with ambiguities. I examine some of them in the following paragraphs by looking at each of the criteria that the theory prescribes as defining an optimal currency area.

We can start our analysis of the criteria provided by the conventional optimal currency area by making a fundamental distinction between the criteria to determine whether a country needs a local currency and the conditions that make the manipulation of such currency viable. The condition of being a closed economy belongs to the latter. There is no reason why a closed economy cannot use an international currency, except for the potential divergence between its business cycles and those of the issuer of the international currency—a condition that is covered by another criterion. There are, however, clear reasons why a local currency may not work in a too open economy. A local currency must meet one of two requisites for the central bank to be able to manipulate the economic behavior of the population through it. One is that it embeds the standard of value of the population; alternatively, the government must be able to force the people to use it. This is the reason why the degree of openness of the economy is important. If the economy is not closed, people can escape the monopoly of the local central bank. People in open economies are too much in contact with international currencies and can introduce them in the country, legally or illegally, weakening the monetary control of the central bank. In any case, I know of no case in which the theory has been used to recommend the abandonment of the local currency, even in countries that are widely open. Thus, in practice, this criterion has been at best irrelevant. At worst, is just an argument in favor of the agents in the principal-agent problem.

Thus, we are left with criteria in two dimensions: size and relationships with the international markets.

Regarding size, we have to recognize that bigness is relative. There are many economies and even regions within countries that are larger than any or most or all the developing countries taken together. China, the largest developing economy, has a GDP of $1.4 trillion and represents 3.9 percent of the world’s GDP, about the size of California. Mexico, the second largest, represents 1.7 percent of the world’s total, 14 percent of the Japanese economy, or 46 percent of that of California. The economy of the Netherlands, a country of 16 million inhabitants, is about the size of that of Brazil, which is only 20 percent larger than that of New York City (and smaller than New York City and Newark together). At $10.9 trillion in 2003, the economy of the United States is 53 percent bigger than all the developing countries combined ($7.1 trillion). The European Union, at $8.3 trillion with the countries it had in 2003, was 15 percent bigger. Taken together, 52 percent of the world’s economy works under two currencies. If we add Japan, which represents 12 percent of the global GDP, almost two-thirds of the world’s economy works under three currencies. The other 38 percent works under more than 100 currencies.1 Many of these countries have a GDP that is equivalent to that of a few blocks in downtown London.

The three big economies are not only larger but also more diversified and complex than the economy of all the developing countries taken together. Like the developing countries, they produce commodities and basic industrial products; in addition they produce sophisticated industrial goods and knowledge-based goods and services. They do it in different regions or, in the case of the European Union, in different countries. Each of these regions or countries is much larger than most developing countries (think of Germany, France or Italy or the region of the Great Lakes). Yet, all these regions and countries share a common currency.

Bigness in itself is not a criterion to determine whether an economy should have its own currency and, if it were, no developing country would reach the minimum size, which would be that of Japan or the United Kingdom.

Thus, we are left with only one dimension of criteria: the relationship with the international markets, which comprise criteria on the business cycles, the geographical distribution of trade and the divergence of external shocks. The three criteria could be collapsed to only one as all of them refer to the risk of external shocks, which may come from the differences in the business cycles and shifts in the geographical distribution of trade as well as from other kinds of events, such as natural disasters. Collectively, using these criteria to create a local currency would make sense only if we assume that monetary management in developing countries can produce countercyclical effects. Unfortunately, this is not the case in most developing countries. There, the classical responses to external shocks of any kind, devaluation, tend to be quite depressive.

In addition to these problems, looking in more detail at each of the trade-related criteria we find that the theory is also vague. It is difficult, for example, to pinpoint what kind of divergence between the business cycles of two places is acceptable within an optimal currency area. The vagueness extends to all other criteria, including the implicit real exchange rates of different regions or cities within a country.

For example, during the second quarter of 2004, the rate of inflation in Houston was 4.31 percent while in San Francisco it was 0.9 percent. The other 12 largest cities in the country had rates between these two. This means that the dollar was appreciating in real terms in Houston relative to San Francisco. The fact that the cost of living is substantially different in different cities and regions in the United States shows that this is not a passing phenomenon. Prices must have grown at consistently higher rates in New York than in Tulsa, Oklahoma to explain the wide differences in the prices of nontradable services in the two places. In the theoretical jargon, the American dollar of New York would be overvalued in terms of the American dollar of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Consequently, New York should be growing at a slower pace than Tulsa. Yet, New York has been more expensive than Tulsa for generations, and it has grown at a faster pace also for generations. Certainly, many activities that were characteristic of New York disappeared in the process as they became too cheap for the city’s costs. One example of this was the leather products industry that used to thrive in Manhattan. That industry disappeared but the city kept on growing by shifting to activities with increasing value added.

In this respect it is interesting to note an optimal currency area criterion that was included in the original statements of the theory but was dropped later: the possibility of migration within the currency area as an essential condition that should be present for two countries to share a currency. The idea was that, since the rate of unemployment would be a function of monetary policy, and this a reaction to the particular stages of the business cycle in the currency area, adopting the currency of some other country would create unemployment in the adopting country when the business cycles diverged. The only solution to this problem was to have free mobility of labor between the two countries. Even if not said explicitly, we can deduct that this job arbitrage would result in an equalization of the unemployment rates across the two countries.

Yet, in the second quarter of 2004, the unemployment rate in New York City was 7.07 percent while in neighboring Boston, Newark, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington D.C. it was 4.37, 4.97, 5.20, 4.43 and 3.07 percent, respectively.2 That is, the unemployment rate of New York City was more than twice as high as that of Washington D. C. and substantially higher than those of its neighbors, including Newark, which is just across the Hudson River. This should prompt a massive migration from the first to all the other mentioned cities. If there is an area in the world where migration is easy that is this region. In fact, many urban economists reckon the region as one single megalopolis. Yet, the substantial differences in unemployment rates do not result in massive migrations within the megalopolis.

Dropping this condition was understandable given these facts. Yet, dropping it seriously damaged the internal logic of the theory. It was the only criterion that referred to the capacity of reaction of the economy to an external shock. The other criteria referred to the shocks themselves, so that by dropping it the optimal currency area is defined exclusively in terms of the problems it can face.

To grasp how badly the theory was damaged by dropping this condition we can look at the currency area built by the dollar in the United States. Given our discussion in the previous paragraphs we can alternatively conclude that the theory does not make sense or that all the cities of the Eastern megalopolis should have different currencies, so that, for instance, New York could devalue its NY$ to reduce its unemployment or appreciate it to reduce its rate of inflation. Since other criteria tell us that the dollar area is as close to be optimal as any area can be, we have to discard the idea of fragmenting it into as many currencies as divergences in growth, inflation and unemployment there are between its regions, cities and neighborhoods. Having access to a hugely diversified economy working under the same currency is what really turns the United States into an optimal currency area. This is what maximizes the possibilities of substitution when the exchange rate moves. This is what allows the financial system to be as large as it is. This is what reduces transaction costs, uncertainties and unexpected monetary shocks between trade partners. Therefore, whatever the differences in growth, inflation or unemployment, it is optimal for these regions and cities to belong to this area. If this is true for the economies of the regions and cities in the United States, which are larger than most developing countries, it should be true for countries adopting the dollar as well. The answer to this assertion used to be that in the United States people can migrate within the currency area to compensate for the asymmetric effects of the common monetary policy. Now that this answer has been dropped, there is no other answer to this assertion. The possibility of internal migrations was the hidden foundation of the conventional optimal currency area.

Now we can turn to measure the divergences of the business cycles of different regions in the world to see whether the theory gives us a clear idea of which of them should have a currency of their own. We can use two important countries that share a currency, Germany and France, as the yardstick to see what is acceptable in terms of divergences in the business cycles. These countries are neighbors, industrial and share the Euro.

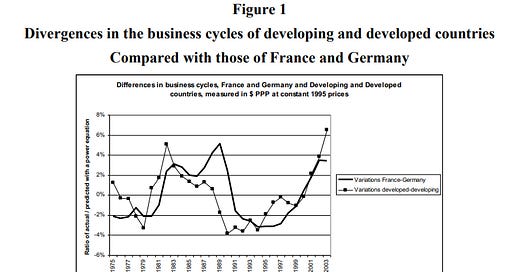

We tend to assume that the divergence of the cycles of developing relative to those of the developed countries is much larger than that between countries that share a currency. Figure 1 shows that the order of magnitude of the divergence between the business cycles of the two leading countries of the European Monetary Union is about the same as the divergence between the developing and the developed countries taken as a whole. Moreover, the two curves seem to coincide, with varying lags, in the direction of their movements.

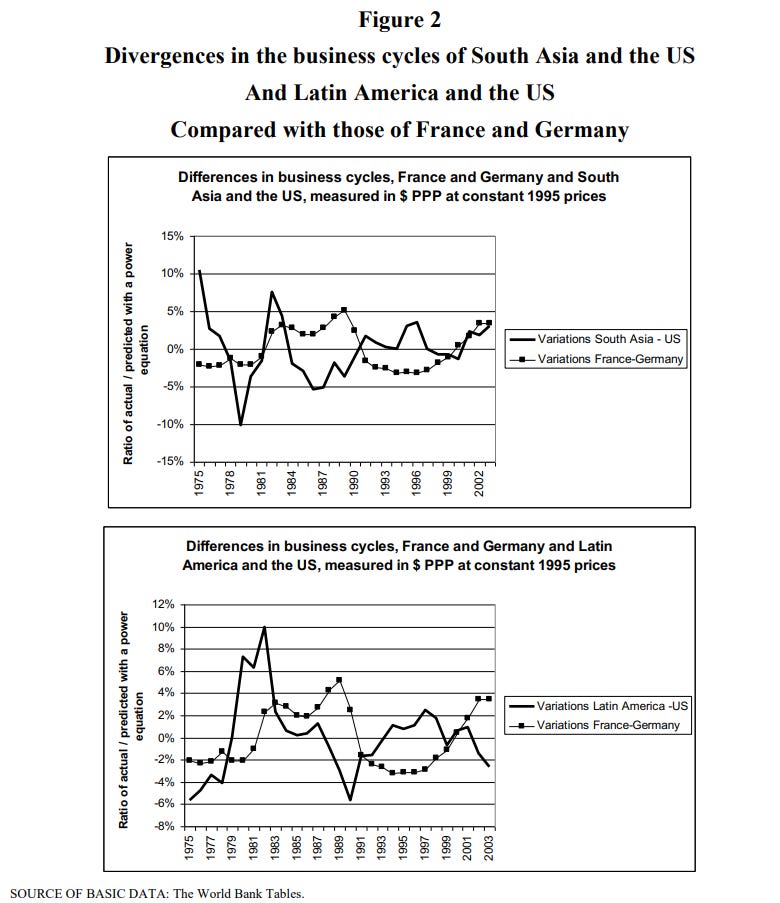

An analysis by regions shows some differences with the aggregates used in the previous Figure. The next three Figures show the divergences between the business cycles of the different regions of the developing world and those of the United States, compared with the divergences between France and Germany. As it is apparent in those Figures, the business cycles of South Asia and Latin America diverged quite markedly from those of the United States during the highly inflationary 1970s and 1980s. Yet, they have been comparable with the divergence between France and Germany since the early 1990s. This shift seems to raise the suspicion that the business cycles of developing countries are heavily affected by their own monetary manipulations. The period of high divergence coincides with one of high instability in the developing countries. As shown in Figures 59 and 60 above,3 these countries suffered from high rates of inflation and large current account deficits during the 1970s and early 1980s. Then, during the 1990s they reduced the rates of inflation and the current account deficits. As they did that, their business cycles came much closer to those of the United States, to the point that their divergences are within the range of those between France and Germany. Based on their performance of the last 15 years, each of these regions could have used the dollar as much as the two European countries use the same currency (remember that the possibility of internal migrations is no longer among the criteria of the optimal currency area).

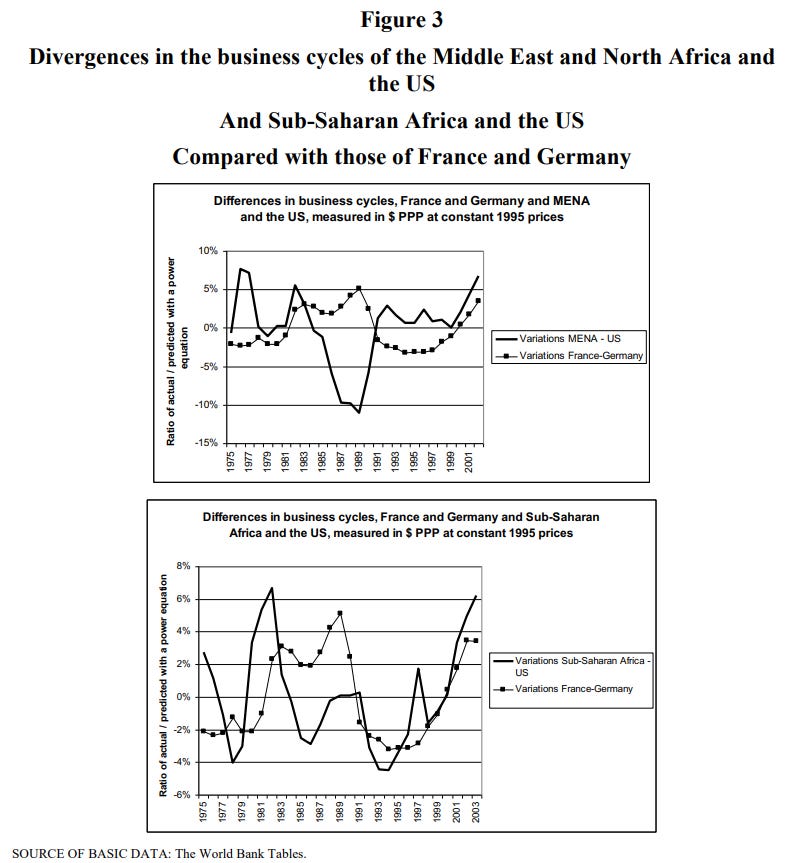

The top panel of Figure 3 shows that the divergence of the Middle East and North Africa followed a path similar to that of the two regions shown above. The case of Sub-Saharan Africa, shown in the lower panel, is somewhat different from those of the other regions. While the divergences of the latter with the United States have been larger at the beginning of the period and smaller at the end of it, the divergence of Africa has been on the same order of magnitude than that of France relative to Germany throughout the period.

The only region that showed consistently large deviations in its business cycles relative to the United States was East Asia and the Pacific, which includes the Asian Tigers. This is shown in Figure 4. There, the differences fluctuated from +10 to - 10 percent in two and a half cycles. The cycles are not just pronounced but they are also frequent. Curiously, however, several of the larger countries in the region, prominently China, peg their exchange rates to the dollar. Thus, with the exception of East Asia and the Pacific, the divergences of the regional business cycles of developing countries relative to the United States are within the same magnitude of the two economies(Germany and France) that most people think are the most closely tied economies in the world.

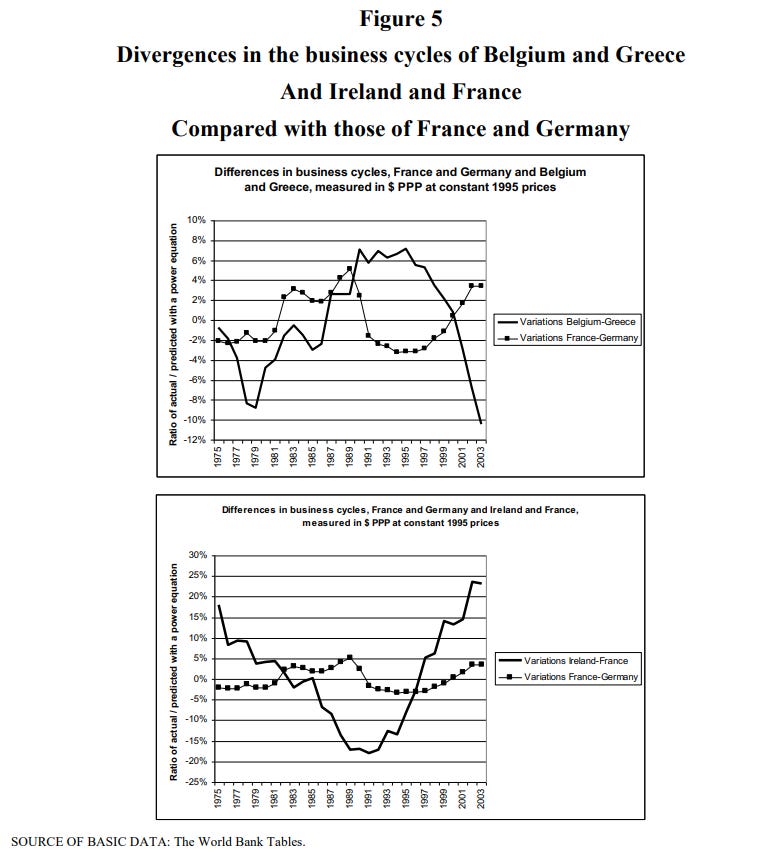

Of course, we can find divergences within the European Monetary Union larger than those between France and Germany. One example, with variations up to 10 percent in each direction, is provided by Belgium and Greece, shown in the top panel of Figure 5. These are of the same order of magnitude as the divergences between any of the developing regions (including East Asia and the Pacific) relative to the United States. The lower panel of the same Figure shows the divergences between Ireland and France, which are of an even larger magnitude. These divergences are about twice the ones we found between East Asia and the Pacific and the United States.

Moreover, the business cycles of developing countries may be much closer to those of a developed country than to a neighboring developing one. Figure 6 illustrates this point in the case of two countries that many people assume should share a currency because their business cycles are very close. The top panel portrays the deviations of Argentina’s GDP relative to those of Brazil and the United States. It is clear from it that Argentina’s business cycles are as far away from those of Brazil as from those of the United States. The deviations against the two countries are quite substantial, having fluctuated in ranges up to -15 to +15 percent from 1975 to 2003.

In fact, as shown in the lower panel, the business cycle of Brazil is closer to that of the United States than to that of Argentina. While in the 1980s the deviations of the Brazilian cycles relative to those of the United States were significant (although less so than those relative to Argentina), since 1990 the range of variation has been around 6 percent (2 up and 4 down).

Both panels tend to confirm the idea that a good portion of the business cycles in developing countries are domestically induced by monetary instability. As the Brazilian economy stabilized in terms of inflation and devaluation, the divergences between Brazil and the United States tended to shrink through the years. Also, they show that the deviations between the cycles of Brazil and the United States were in the same order of magnitude as those between Belgium and Greece even during the initial period of Brazilian high instability—an instability that would have not taken place if Brazil had had a stable currency. Since the stabilization of the mid-1990s, the Brazilian cycles have been extremely close to those of the United States. If we applied the logic of the business cycles to Brazil, it seems that the dollar would be a better currency for this country than a Mercosur hybrid, which would lead to protracted conflicts due to the large divergence with the cycles of Argentina.

The Netherlands provides an example of a successful mix of commodity and sophisticated industrial and agricultural production within a single monetary area, even if those products tend to have different business cycles. This is a good example because the monetary problems generated by the conflicts between the prices of the commodity this country produces (oil) and the rest of the economy were vilified with the name of the Dutch disease. This disease was pronounced incurable. And it is so when seen through the looking glasses of narrow trade models. Yet, the patient not only did not die but instead attained an impressive transformation into a highly sophisticated economy based on knowledge. It even succeeded in competing with the developing countries in the production and marketing of another commodity, flowers, a field in which the latter seemed to have all the comparative advantages. This feat was attained with the strong Dutch local currency, now substituted by the Euro, with a soil that freezes for a long period every year, in a country where the sun disappears behind clouds for months and where land is more scarce and expensive than in any developing country, and where salaries are many times higher than in those countries. It would be difficult to argue that the Netherlands should have had a currency with its value based on the price of a commodity, in this case oil, as many propose developing countries should do. The interaction between the different sectors of the highly diversified Dutch economy provided the solutions for both oil and the traditional activities that this threatened.

Thus, if the case of Europe establishes the limits to which divergences in the business cycles are acceptable within a currency area, it seems that most developing countries are well within such limits in relation to the dollar and the Euro.

There is another dimension of the problem of the divergences between the rates of growth of different countries that, while not included in the formal criteria to have a local currency, is taken as a reason to devalue a currency in the long term: the divergence not in the business cycle but in the long-term growth trends. The idea is linked to the relative growth of productivity between two countries. It prescribes devaluation when a country’s total factor productivity is growing at a slower pace than those of their trade partners or competitors. The prescription is based on the notion that if the relative productivity of one country is declining, it would be left with nothing to do, as all their activities would be taken over by its competitors. The only solution is to devalue the currency to reduce the real wage of the population, turning the country competitive again and thus preventing unemployment. That is, following this logic, countries must have a currency to adjust for changes in their total factor productivity relative to that of other countries.

This idea, however, ignores that monetary instability may affect total factor productivity. As we discussed in Part I, continuously devaluing the currency to keep the existing activities profitable blunts the market incentives to advance to a higher stage of value added. Japan tried that strategy in the first few years after World War II and then abandoned it, aiming at a strong yen. The shift in strategy was successful. In fact, no country has developed based on a weak currency.

Moreover, devaluing the currency would lead to higher rates of interest, higher inflation rates, lack of long-term credit, higher external debt burdens and higher economic volatility, all of them events that tend to reduce the total factor productivity. Following this prescription, which theoretically seems unbeatable under its own assumptions, would condemn countries lagging in productivity growth to a low-level equilibrium.

It is important to note here that, because of comparative advantages, countries can always find activities where, with their resource endowment, they can be more productive than others. The incentives to make the shift, however, must be there.

Regarding external shocks, most economists assume that the existence of a local currency gives countries more flexibility to adjust to them. Yet, this assumption does not follow mathematically from theory. It is open to empirical evidence, particularly in developing countries, where devaluation means increased interest rates and pressures to increase wages, among other reasons why devaluations may be depressive in those countries.

For example, the evidence shows that these assertions are untrue in Central America and the Caribbean. A recent study of the subject analyzed the long-term vulnerability to external shocks of the countries in the region. The analysis was conducted when El Salvador had not yet dollarized. Yet, it had had a de facto fixed exchange rate for several years, so that four different regimes were present in the region: dollarized (Panama); fixed rate (El Salvador); and crawling-pegs and floating the rest.4 The study defined Panama and El Salvador as “credible pegs” to differentiate their regimes from those of the other countries. It reached the following conclusions:

“As expected, changes in terms of trade are positively correlated with changes in GDP. The coefficient of the interactive term [a dummy variable that is one when the country has a truly and credible fixed exchange rate and zero otherwise], however, is negative (although not statistically significant). This suggests that in our sample of Central American countries, more flexible regimes are no better than fixed ones in terms of the ability to protect the economy from external shocks.”5

Regarding the cyclical behavior of interest rates, the authors of the study say, “…we find a significant anti-cyclical interest rate in Panama and El Salvador (Panama is dollarized and El Salvador has a formally flexible but de facto fixed exchange rate), pro-cyclical in Costa Rica (which has a crawling peg) and neutral rate in Guatemala (which has a flexible exchange rate).”6

In general terms, the study concludes: “Our analysis suggests that beyond the reduction in inflation, dollarization may reduce financial fragility by reducing the volatility of key relative prices in the economy, as well as to contribute to the development of the financial system. Although higher inflation and more volatile relative prices are clearly undesirable outcome under flexible exchange rate regimes…they might just be the result of a rational choice, in which the government decides to trade some credibility for more monetary independence and output stabilization. The analysis [of this paper], however, seems to indicate that this is not the case. The Central American countries with flexible exchange rate regimes appear to be worse off than their counterparts with credibly fixed regimes [Panama and El Salvador] in terms of the volatility of their nominal variables, without any noticeable gain in terms of the volatility of the real variables. We therefore conclude that although Central American countries with flexible regimes paid large cost in terms of credibility, they did not appear to gain very much in terms of the benefits of monetary independence.”7

Among the results of this study it is interesting to focus on the conclusions about the relationship between the interest rates and the economic cycles. Contrary to what everybody expects from the assertions of conventional theory, the rates of interest in the countries that did not devalue during the period of the study were anti-cyclical (that is, they were low when the economy was in a downswing and higher when it was in the upswing) while those of the crawling peg were pro-cyclical. They increased when the rate of growth of the economy was declining. This is quite logical in the real world. It was during the downswings that the countries with the crawling peg devalued the most. With the standard of value set in the foreign currency, the rates of interest tended to increase with the devaluations, making for the anti-cyclical response of interest rates.

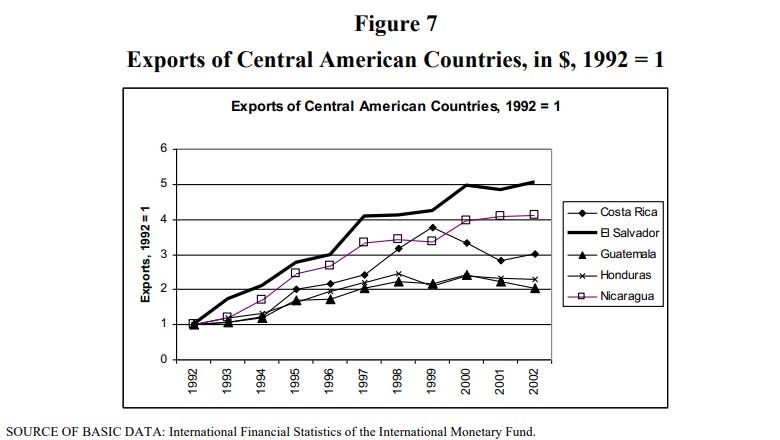

Regarding the adjustment in trade, the study concludes that the flexible rates were no better than the fixed ones to protect the country against shocks in this dimension. We can confirm this conclusion with the countries that are more comparable in the region in trade terms, those that are members of the Central American Common Market. Figure 7 shows how all of them suffered from trade setbacks since 1992. Yet, as it is clear in the Figure, El Salvador not only outperformed all the other members (all of which devalued repeatedly during the period) in terms of overall growth of exports but also experienced lower volatility.

In fact, the adjustment to external shocks through devaluation suffers from all the problems associated with devaluations that we have discussed throughout the book, including prominently the transference of the standard of value, the reversed liquidity trap and all its consequences.

The case of Central America shows that it should not be assumed that flexible exchange rates actually deliver higher protection against external shocks. In fact, the depressive responses of developing countries to devaluations suggest that this is not true generally. The burden of the proof that they help in dealing with external shocks must be placed on the local currencies.

The geographical distribution of trade is included among the criteria because of reasons that are closely related to those of the business cycles and the external shocks. The idea is that countries must have currencies that move as closely as possible with the currencies of their trade partners to avoid situations in which their nontradable costs put them out of competition. There are two possible policy conclusions from this reasoning: one is that countries must share a currency with their main trade partners; failing to meet this condition, they must have a local currency that they can devalue if the trade partners devalue. If the currencies of their trade partners move in different ways, then the best policy is to take a weighted average of these movements and change the value of the currency in accordance to such average. Appreciation when the partners appreciate is rarely advised although it may happen if the country uses an automatic formula to adjust its currency. In reality, however, the case is also rare.

The case for devaluation when dealing with shifts in the geographical distribution of trade seems compelling. Yet, as in the rest of the criteria of the optimal currency area, such case depends crucially on the ability of developing countries to counterbalance the business cycle, trade problems and external shocks. This ability is quite weak and efforts to apply it prove counterproductive in many cases. As we discussed before, developed countries have this ability because an international currency gives access to a thoroughly diversified economy, so that when it is devalued the substitution effect of the devaluation (the substitution of local production for imports) predominates over the income effect (the increase in domestic prices). This is not so in developing countries, where devaluations tend to be depressive, inflationary or both. It does not make much sense to increase interest rates and the burden of the external debt to counterbalance a depressive shock. Thus, it is much better to share a currency with trade partners or, alternatively, belong to a currency area with a well diversified economy, which would allow for substitution effects to overcome the income effects of shifts in the exchange rates. Such a currency area would be truly optimal, much better than one where income effects are the main response to these shifts

In summary, the features of the actual currency areas in the developing countries are far from optimal even if all of them are optimal in accordance with the optimal currency area theory. They are so far away from optimality that people spontaneously substitute their currencies with foreign ones in their domestic operations even if this introduces substantial foreign exchange risks. People, however, find it better to face those risks than to save and operate financially in the official currencies of the supposedly optimal currency areas. That is, people assess the risks posed by the local currencies as higher than the exchange rate risks, which we know are substantial.

These problems should be sufficient to revise this theory. Definitely, no country aiming at reducing the risks posed by the globalized world should use it to choose its currency regime. The issues involved in such a choice are much more complex than those contemplated in the limited scope of the theory. As a manifestation of the incompleteness of the theory, the decision to adopt a local currency, which is as far as the theory goes, is not sufficient to resolve the problem. Such decision triggers the need for many other decisions, some of them having to do with the monetary regime, some others dealing with specific challenges. In this way, countries taking this option would have to make a decision on the way they would manage their currency. A first dimension of the choice is whether they will stick to a certain foreign exchange regime or will change it from time to time—changing, for example from fixed to floating or a sliding peg depending on the circumstances. Then the decision of what shape the regime would take (permanently or initially) would be needed. All of these decisions, of course, would be linked to decisions regarding the stance the government would take regarding the objectives of monetary policy. The monetary policy could target, among other objectives, a certain inflation rate, the level of interest rates or an exchange rate to a foreign currency. Not all of these options are open for all the foreign exchange regimes. Once these decisions were made, the governments would still need to put numbers to their policies. And then, each time that there is a relevant event in the international or domestic markets, they would have to make decisions on how to manipulate their instruments to best face the challenge. These decisions would become more complex as the countries integrated with the international markets because the increased number of currencies involved would affect the relative prices of inputs and final products. Each shift in the exchange rate relative to all other the currencies would create both income and substitution effects. The possibility of converting the former into the latter diminishes with the number of currencies the country would have to deal with. Moreover, the complexity of these effects easily overcomes the capacity of macroeconomic models to predict and even measure their impact on the welfare of the countries. Finally, the theory would say nothing about the relationship between financial and trade variables that should exist in the monetary regime, except for stating that borrowing abroad is a source of exchange rate rigidity.

At the end, one discovers that the optimal currency area can be optimal only if the currency is managed optimally, case-by-case, event-by-event, day-by-day. And, still, optimality would be in the eye of the beholder because the theory does not say a word about the subject. It is well known that macroeconomists that passionately believe that currencies must be managed may hold extremely different opinions on how this management should be conducted in any given set of circumstances. Of course, all of them believe that the currency should be flexible. But their opinions will always diverge on the particular way in which the currency would be flexible and on what should be the monetary policy that should be applied within such flexibility. These issues, and many others, will always be present.

Moreover, the designers of a currency regime cannot assume that future governments will manage the exchange rate so as to adjust smoothly to external developments all along. In reality, the management of the exchange rate opens many other possibilities, some of them very perverse, which appeal to politicians. As history proves, governments may decide to appreciate a currency to reduce inflation and generate a domestic boom. This is irrational in the long term but may be rational politically in the short term—generating the boom to win elections, leaving the task of dealing with the subsequent crisis to the next government, for example. We know that these cases are not rare in the developing countries. The only consolation would be that, according to the theory, the currency area would be optimal regardless of what the central bankers or politicians do with the currency. In this sense, the theory is reassuring. Now we can turn to look at the features that make for a truly optimal currency area. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Toward a Redefinition of an Optimal Currency Area

The objective of a monetary regime must be to maximize the probabilities of a smooth adjustment to the unpredictable developments of a globalized economy. The optimal currency area theory seeks such flexibility through the freedom of the currency to change its value relative to that of the others. As we have seen in the previous chapters, this approach has failed in most, if not all, the developing countries. In fact, the theory provides little guidance beyond rating as optimal regions that share some common external problems.

As we discussed in the previous chapter, we need a definition of what an optimal currency area is, based not on the features of geographical regions but on the quality of the monetary environment. That is, a currency area must be optimal not because its members share the same problems but because they obtain optimal services from the currency that covers it. This is what I do in this chapter.

To identify these features we can look at the experience of the successful currency areas: those covering the United States, Europe, Japan and the United Kingdom. Drawing from this experience, we can say that a currency area would be optimal if it maximizes the possibilities that substitution effects would dominate the income effects coming from external shocks of any nature (divergences in the business cycles, devaluations of other currencies or changes in the patterns of trade of trade partners). The maximization of such a possibility is what turns optimal a currency area both from the trade and the financial points of view.

From the trade perspective, if some exports markets suddenly disappear (as a result of a devaluation of their currencies, for example), optimality would mean that exporters would be able to find other markets within their own currency area. This also applies to imports. If some of these become too expensive, the currency area should be able to substitute for them at the equivalent prices and quality, so that neither consumers nor producers would suffer from significant price increases.

Size and diversity also help to absorb changes through other mechanism. The larger and more diversified an economy, the less it will be affected by drastic changes in one sector. If a technological advance turns obsolete some products (like slide rules or dedicated word processors, for example), a large and diversified economy would be able to absorb their disappearance with lesser macroeconomic effects than those that a smaller economy would suffer. The fact that different products have different business cycles helps to ensure that no one of them would bring down aggregate demand. This makes the system more stable for everybody.

Contrary to what could be surmised, this criterion does not prevent countries from trading with other currency areas. The volume of trade among the three major currency blocks is enormous. Diversification, however, helps them to absorb any shock that can come from the other two blocks. The American economy provides an enormous natural hedge to American exporters to Japan. Smaller and less diversified economies cannot provide such hedge.

On the financial side, the criterion of diversity would mean maximizing the access to large and deep financial markets, capable of providing credit at all maturities and at different levels of risk as well as derivative instruments to manage the latter. In addition to facilitate development through the access to deep financial markets, having an identity between the currency used in domestic and international operations would resolve one of the main problems now faced by most developing countries. Obviously, such identity eliminates the risk of a sudden shock caused by exchange rate movements on the burden of the external debt. This would increase the efficiency of exports in promoting economic growth, as a part of them would not have to be used to pay for the additional burden of debt caused by devaluations relative to the currency of international borrowing. Moreover, the access to a large and diversified financial system allows people within the currency area to explicitly hedge their foreign exchange risks in their operations with other currency areas. They can hedge many other risks as well, which they cannot do in a small monetary environment.

The interaction between the trade, monetary and financial dimensions would also be optimal and mutually reinforcing in this conception of the optimal currency area. With substitution effects dominating the income effects, the inflationary pressures would be much weaker, facilitating the task of keeping inflation rates low and real wages stable. This, in turn, would allow the domestic currency to become a standard of value. This would help in keeping the interest rates low even when the currency is devalued.

Thus, the degrees of freedom of adjustment to external shocks can be maximized through a completely different and much simpler approach than the continuous adjustments advocated by the conventional optimal currency area. Rather than adjusting individually to each change, trade resilience can be attained by maximizing access to unrestricted diversification within the same monetary area. This, in turn, would maximize the probability of turning income into substitution effects whenever there is a trade shock.

This maximization would be the only criterion in the choice of both a currency regime and the currency that would give reality to it. Maximizing such access would be necessary and sufficient to choose a currency.

That is, under this other approach to the optimal currency area, the criterion to choose a currency would be that the area covered by the chosen currency must be as large and diversified as possible.

Notice that this condition diverges from the criterion of size in the conventional optimal currency area in two dimensions. First, it includes both size and diversification. Second, size is not taken as a criterion mandating the creation of a local currency once a critical size has been reached. Instead, it is a magnitude that the chosen currency must maximize. In the sense I am giving to the criterion, a currency covering two large countries is better than one covering only one of them. It makes the point that, because of economies of scale and diversity, the Euro provides more services for each of its users than the sum of the services of the currencies that it substituted. It gives all the services of each of these currencies plus the overarching ability to reduce transaction costs as well as to open more possibilities of substitution among inputs and outputs within the same currency area.

Looking at the optimal currency area from the perspective of diversity also creates a sharp contrast with the conventional views on the desirability of sharing currencies across countries with different degrees of development. Asymmetries in the economic features of the countries that join the currency area are not undesirable when the issue is looked at from this perspective. Under the conventional approach, it is frequently assumed that competing countries tend to share business cycles and external shocks, so that if they decide to share a currency with someone, it should be with similar countries, a la Euro. As we saw in the case of Europe, the assumption that countries with similar economies tend to have the same business cycles is not based on reality. More fundamentally, however, while sharing a currency area would be profitable for competing countries, it would be even more so for countries that are in different stages of development, are complementary in trade and have diverging business cycles. The uniform monetary space would help them to create international chains of production with the certainty that the relative prices of inputs (among them and relative to the price of the output) would not be disturbed by arbitrary decisions made in central banks. Thus, mixing countries producing commodities with industrial countries would be ideal from the point of view of trade.

The identity of the currency used in trade and financial operations would render additional benefits in terms of trade. One of them would be that there would be no conflicts for traders between the two aspects of monetary matters. The other would be that a deep financial market would allow traders to hedge those risks that they would be forced to take. A third one would be that exporters, operating in a deep financial market, would be able to provide financing to their customers, something that is a problem in all developing countries. David C. Parsley and Shang-Jin Wei provide a fourth advantage. In a recent paper, they show that currency unions result in a closer and faster price convergence among the participants.8 Since prices are a major source of information for exporters and traders in general, trade is facilitated when the prices prevalent in the domestic market are similar to those in the export markets. By adjusting their production functions to be profitable in the domestic markets, producers can be profitable in the foreign ones as well.

Of course, short-term capital flows, which worry the supporters of the optimal currency area to the point of prompting them to ban their flows, would not be a problem. A big and diversified currency area eliminates the contradictions now present between what the conventional theory says is optimal and financial flows.

Within this environment, the stability of any transformation would be guaranteed. Macroeconomic problems would not trigger lethal currency runs. This would reduce the probabilities of having financial crises and would reduce their costs if they become inevitable. The absence of the nonlinear effects of the fear of devaluation would restrict their impact and simplify their solution.

Moreover, spontaneous dollarization, now a big threat to the monetary stability of countries, would disappear.

Having defined what an optimal currency area would be, we can turn to look at the features of the currency itself that would make it eligible to create an optimal currency area.

The first such feature should be that, regardless of its exchange rate volatility, the currency must provide domestic price stability (considering as domestic all the goods and services available in the currency area), as well as low interest rates. Obviously, the size and diversity of the area helps in meeting this criterion for the reasons exposed in the previous paragraphs, particularly the elimination of the income effects of exchange rate movements. Yet, it also requires that the monetary policy applied by the issuer should result in low levels of inflation.

The second feature would be liquidity—which is, the largest possible number of people must accept the currency. The optimal in this respect would be a currency that is accepted all over the world.

Given these conditions, the rate of devaluation or appreciation of the currency relative to other international currencies is not relevant within a wide range. Of course, there is always a magnitude of depreciation that will impair the substitution effect, so that inflation will increase, triggering a host of undesirable effects. This range, however, has proven to be very wide in the last several decades.

Table 2 summarizes the conditions that make for an optimal currency area from the point of view of the diversification of risks.

It could be objected that the criterion of access to a large and diversified economy assumes that all the countries belonging to an optimal currency area would be totally open to trade with those sharing the same currency. It does not. What the criterion says is that maximizing such access should be the primary consideration in the choice of currency. The access provided by all the potential currencies, including the local one, should be compared with each other and then the decision should go in the direction of the currency that maximizes it. In most cases, we can be sure that the local currency would not the chosen one. We can also be sure that also in most cases this would not be a currency issued by a group of developing countries.

Moreover, in a series of papers on the subject, Andrew K. Rose has shown that common currencies promote trade between the monetary partners in magnitudes that he himself finds extraordinary. He has proved this point with gravity models as well as with meta models that include the results of studies carried out by many other scholars on the subject. The analysis of the point is marred by the scarcity of data regarding currency unions, which have been rare. Yet, the results are so strong statistically that the probabilities that he might be wrong are negligible.9

Thus, countries can choose between two different approaches to attain a smooth adjustment to the unpredictable developments of the modern globalized economy. The first, based on the conventional optimal currency area, seeks resilience through creating independent, flexible currencies that could fluctuate against the other currencies. The second, based on a different interpretation of what is an optimal currency area, seeks resilience through the maximization of the substitution effects and the minimization of the income effects of external shocks. The best course to attain these objectives is to adopt an established international currency.

In the conventional theory, optimal currency areas are determined by the characteristics of regions; in the other approach, they are determined by the features of a currency and have no geographical limits. In fact, while the first approach aims at maximizing the fragmentation of currencies subject to an unspecified lower limit to the size of the economies that can have one, the second approach aims at maximizing size and diversity within the same monetary areas, so that these improve as they become larger. The focus of the first is on the possibility of manipulating economic behavior through variations in the supply of money and shifts in the exchange rate; the focus of the second is to assure that money provides the services it is supposed to provide. The first creates tensions between the trade and the financial sides of currency choices; such contradiction does not exist in the second. The first one affords a seigniorage; the second does not. The first reassures countries that by having a local currency they are within an optimal currency area; the second provides access to a truly optimal currency area.

Developing countries tired of being an optimal currency area in the midst of obvious suboptimal monetary conditions have two choices regarding their integration into a truly optimal currency area. One is to create it. The other is to enter into an existing one, which means adopting one of the major international currencies. Creating an optimal currency is obviously more difficult than adopting an existing one. Actually, it may be impossible for most developing countries to generate it because they lack the necessary size and diversity. To be fully diverse, a developing country aiming at creating an optimal currency area would have to entice some developed countries to adopt its currency. The probabilities of this happening are zero.

Thus, becoming part of an optimal currency area entails adopting an international currency. In practical terms, this means adopting the dollar, the Euro or the yen. Some countries may also consider the Pound Sterling.

The particular currency that a country should choose once the decision to become part of an optimal currency area has been taken should be the one that is naturally related to the country’s economy in trade and financial terms. If there is a contradiction between the two, the choice should favor the one that is the standard of value of the population. This would give finality to the decision.

This sounds extreme but only because we grew up in a world in which having a currency is considered essential. For this reason, the burden of the proof is placed on the arguments in favor of joining an already developed international currency area, as if the natural thing were for each country to have its own currency. In fact, monetary fragmentation is the source of so many problems that the burden of the proof should be on the other side. The question should be why a small and poorly diversified economy (as all developing economies are) should create a currency when having access to a well established international one.

Of course, a country adopting an international currency would not have the ability to conduct monetary policies. Given the problems that monetary policies have created in the developing countries this could be taken as one of the advantages of joining an optimal currency area.

It may be objected that the problem is not just that the country would not manage its own currency; it would be that the issuer of the currency would manage it in ways that could be contradictory with the country’s circumstances. That is, the issuer might apply restrictive monetary policies when the user country would be needed an expansionary one. This argument forgets four things. First, that monetary management in developing countries has failed to produce countercyclical behavior. It does not make sense to miss the ability to conduct policies that result in higher interest rates when lower ones are needed. Second, the argument ignores that the range of variation of interest rates in international currencies are just a fraction of the range of variation of the rates in the local currencies. Third, interest rates in developing countries tend to be higher than the international ones, regardless of the phase of the cycle. Finally, developing countries cannot defend themselves against a rise in the international interest rates. While interest rates may increase in developing countries as the international rates go down, those countries can reduce their rates when the international ones are going up only at the cost of accelerating the substitution of international currencies for the local one, domestically or through capital flight. In a world of reversed standards of value, the movements of domestic interest rates relative to those prevailing in the international markets do little more than shifting the currency composition of the supply of financial savings.

Thus, the range of the outcomes of losing the ability to conduct monetary policy spans from irrelevant to positive in most developing countries.

The official adoption of another country’s currency, however, may be politically difficult because it elicits strong emotional reactions in developing countries. Curiously, there is a contradiction between the public posture and the individual choices in these countries. Publicly, most people in those countries reject the idea of dollarization; privately, however, they deposit large portions of their savings in foreign currency accounts, engage in contracts denominated in foreign currencies and judge the adequacy of their sources of income denominated in the local currency (profits, rents, interest rates and wages) based on the standard of foreign currencies.

People reject in public what they do in private because there is the idea that having a currency is as essential to sovereignty as the flag and the national anthem. The association is strange because, as we discussed in the Introduction, local currencies have been the vehicle through which many developing countries have lost their economic sovereignty to the IMF. There are few developing countries that do not have to clear with the IMF their economic policies, and they have to do so because of problems created by their local currencies. With those exceptions, the IMF representative and its mission leaders are more important than the governor of the central bank and minister of finance combined because if the former do not agree with something that the latter two propose the country loses access to the IMF credit and, with it, to the international markets. This is hardly conducive to sovereignty. Many civil society organizations blame this dependence on the IMF. It, however, stems from the problems created by the countries themselves and their penchant to manipulate their currencies in ways that turn them dependent on the IMF. On average, local currencies have been source of dependence, not of sovereignty.

Moreover, the provision of true money is a service that can be outsourced. The important thing is to have such a currency, not the source of it. The idea that the issuer could manipulate the currency in such a way as to harm the interests of one of its users is outlandish. Such manipulation would produce more damage in the issuing country than in the user one.

There are also vested interests that oppose the adoption of a foreign currency. Local banks tend to be the most prominent among these. The rationale for this opposition is that weak local currencies act as protective barriers against foreign competition. Typically, international banks shy away from committing strong currencies in massive commercial operations in developing countries. Where they operate, they finance their operations with local currency exclusively, so that they become part of the local banking system, subject to the same constraints imposed by the weakness of the country. The common mechanism to do this is to commit the minimum capital and then extract it back through services provided by the international headquarters. They commit foreign exchange resources only to a small number of elite exporters and to companies with which they have ties abroad. Their behavior is rational. Channeling large amounts of foreign exchange to the domestic market would expose them to the foreign exchange risks of currencies against which there is no possible hedging. This, of course, keeps the margins of intermediation comfortably high in the local markets. Local banks can be profitable even if they are highly inefficient. With the adoption of an international currency, the exchange risk is eliminated and transferring money from abroad becomes attractive for international banks. Margins of intermediation go down and the market is spoiled by competition.

There is no need to emphasize the strength of the opposition coming from the people in charge of monetary management, their advisors and the people who aspire to be one of them.

Politicians are also enticed by the possibilities open by the ability to create money. It allows them to collect the inflation tax, the only tax they can apply without having to obtain the approval of the national assemblies. Using the central bank as a source of unlimited credit for their pet projects and sectors is quite attractive. Once they discover the powers of sterilization, and particularly the ability it gives central banks to create credit for certain sectors and withdraw it from others, in a nontransparent way, they tend to love it too.

Thus, even in countries where people reveal their preference for an international currency dollarization may pose a political problem.

The possibility of creating regional currencies within the developed world has been proposed frequently. This proposal appeals to the myth of monetary sovereignty. Yet, even in those terms, it is inadequate. There is a qualitative difference between managing a currency and half-managing it. As we discussed in the case of Ireland, having a seat in the board of a central bank with several members cannot be called managing a currency. Trying to define policy opportunistically to meet each challenge, (as the optimal currency area would have it), can only result in chaos and protracted internecine conflicts. Just take a look at the differences between the business cycles of Argentina and Brazil and then picture the discussions in the board of directors of a hypothetical Mercosur Central Bank. Think of the weight of the opinions of Paraguay and Uruguay in such a bank. Think of the demands for credit of all countries to finance their fiscal deficits. Then imagine what would happen if one of the countries experiences a banking crisis and demands monetary creation to meet it—using dollar reserves of the entire community to save the banks of one of the members.

In fact, the only way to manage a regional central bank is adopting impersonal rules, such as keeping the rate of inflation low throughout the currency area. Two of the rules would have to be that the communal central bank would not lend to the ministries of finance of the member countries and would do nothing in case of a crisis in one of these members. Otherwise, the set of incentives would be tilted in favor of imprudent fiscal and financial behavior. All the members would try to maximize their share of the credit of the collective central bank. Thus, the only viable solution is to impose the impersonal rules. Once these are established, each and every member of the board becomes irrelevant in terms of defining policy. Their only role would be applying the rules. That is, to be effective, the central bank would have to be the equivalent of a foreign one. This is the case of the European Central Bank, which does not lose its sleep if one of its countries is having exchange rate problems. Rightly, it focuses on the quality of the currency, knowing that if it deteriorates, all the members would suffer and the Euro would lose its legitimacy as currency.

More fundamentally, aiming at creating an optimal currency area putting together a group of developing countries is as unrealistic as trying to create it within a single country. Even if all the developing countries joined together to create such a currency area, this would still be wanting in terms of size and diversity. The income effects would still dominate the substitution effects of devaluations. The currency would lack demand beyond the geographical borders of the currency area and the financial depth of a true international currency. Thus, it would still require financing in international currencies, so that the foreign exchange risk would remain embedded in the financial operation of the country. Devaluations would still increase the burden of the external debt.

For these reasons, forming monetary unions of developing countries exclusively, although in the first moment could be instruments to raise the self-esteem of these countries, does not seem to be a promising idea.

In summary, a truly optimal currency area is defined not by the commonality of problems across geographic regions but by the quality of the currency serving it. Such quality depends on its ability to keep inflation rates low and its acceptance high across a large and diversified economy, thus maximizing the possibilities of substitution in production and consumption within the area itself. Financially, the currency must provide access to deep and broad financial services and credit.

Three or four such areas already exist—the dollar, the Euro, the yen and the Pound Sterling. Adopting one of them is the only practical possibility that developing countries have to access to an optimal currency area. The decision is theirs.

Conclusions

Developing countries can opt for two radically different monetary strategies to cope with the uncertainties of the increasingly globalized world. The first is to follow the prescriptions of the conventional optimal currency area theory, keep a local currency and then try to manage it in each future event in such a way that it maximizes the smooth adjustment to changing circumstances. The idea is that counting with a local currency will help them to pursue the optimal monetary policies for each circumstance and let the exchange rate to absorb any imbalance that such policies could create relative to other countries.

This approach has worked for developed economies with large and diversified economies. These countries are able to pursue countercyclical monetary policies independently from what other countries are doing. In this way, when affected by a negative event (such as a downturn in the business cycle), they can increase the supply of money and reduce interest rates, letting the currency to depreciate. The depreciation itself does not affect the domestic monetary and financial variables. The rates of inflation and interest remain low and the real wage remains unchanged in domestic real terms. The devaluation, however, triggers a substitution of domestic production for previously imported goods and services and improves the cost structure of domestic producers relative to those of other countries. The net result is that the economy recovers, pushed by the substitution effect in the domestic demand and by the lower costs in exports demand. That is, these countries can use monetary instruments to conduct countercyclical policies within an overall stable environment.

This is not the case in developing countries. There, local currencies have failed to deliver the promises that the optimal currency area theory and the associated system of floating currencies made on behalf of them. This failure is in part due to the abusive management of monetary policies that has characterized the average developing country. This has eroded the public’s trust in the currency. It is, however, also the result of the structural weaknesses of these currencies. Such weaknesses are related to the small size and poor diversification of the economic areas the cover. Because of this problem, the devaluations that reactivate the economies of developed countries produce large negative income effects in the developing ones, which in turn translate into higher rates of inflation and depressive increases in the rates of interest and reductions in the real wages. The net result of these problems is that local currencies have been unable to establish themselves as standards of value in their own domestic markets. Such role has been transferred to an international currency. This, in turn, has led to the reversed liquidity trap, an endemic problem in developing countries that becomes deadly in currency crises that trigger financial crises. The conditions of the reversed liquidity trap are such that the creation of the domestic money worsens liquidity crises as it increases the domestic price of the scarce liquid commodity, foreign currency. In many countries, the threat of the endemic reversed liquidity trap has become manifest in the spontaneous dollarization of the domestic financial operations.

These problems question the adequacy of the optimal currency area theory. While the theory assumes that the economies of the developing countries will react in the same way as those of the developed ones to the monetary impulses, reality shows that this assumption is not warranted. On the contrary, because of the small size and poor diversification of these economies and because their local currencies have not been able to establish themselves as standards of value, monetary policies tend to produce perverse results. Against the evidence of this behavior, the conventional currency area is based on the assumption that these policies produce the intended results.

Having made this unwarranted assumption, the optimal currency area theory defines optimality in terms of the features of geographical areas, aiming at identifying regions that share problems that could be resolved through common monetary policies—assuming, of course, that such policies would have the power to resolve them. In the process, the theory forgot to define what an optimal currency area would be in terms of the services that the currency would provide to its users. When comparing what those services would be with the reality of most developing countries we find that they live in supposedly optimal currency areas within substantially suboptimal monetary services.

Reversing the process of analysis, starting first with the definition of what an optimal currency area would be to then find how to integrate a country to it we reach conclusions that are completely different from those of the conventional optimal currency area theory. In this book, we defined an optimal currency area as one that would provide access to a large and diversified economy, which in turn would have two consequences. First, this would maximize the dominance of substitution effects over income effects in the adjustment to events outside the currency area. Second, this would also provide access to all the financial power of a diversified economy, allowing countries to meet all their financial demands within the same currency area. This would eliminate the exchange rate risks of the external debts, which is a source of perpetual worry in a country with a local currency.

The features that currencies need to have to create a currency area of this kind are two. First, the currency should be managed in such a way as to avoid high rates of inflation. Second, they must be liquid across a large geographical area, preferably around the world. Within a wide range, the rate of devaluation or appreciation relative to other international currencies is not relevant.

Within this conception of optimality, the number of optimal currency areas collapses from more than 150 to three or four: the dollar, the Euro, the yen and the Pound Sterling. If developing countries want to have access to an optimal currency area, they should adopt one of these currencies.

By doing this, they would renounce to manage their own currency and would forego their seigniorage. Given the poor experience that developing countries have accumulated regarding the management of their currencies, losing the possibility of running such policies is actually a benefit of dollarization. Regarding seigniorage, the loss is minimal in countries with sound financial and fiscal policies. As we discussed before, what can be substantial is the loss of the inflation tax, which, in any case, should be substituted with a more efficient way of taxation.